The Digital Museum of U.S. Highway 50 is an exploration of Highway 50’s cultural history corridor, not only to understand the many subcultures along the highway’s path, but also as a means of understanding the United States’ history as a whole, by treating the highway as an objective framework to…Continue reading “About the Museum”

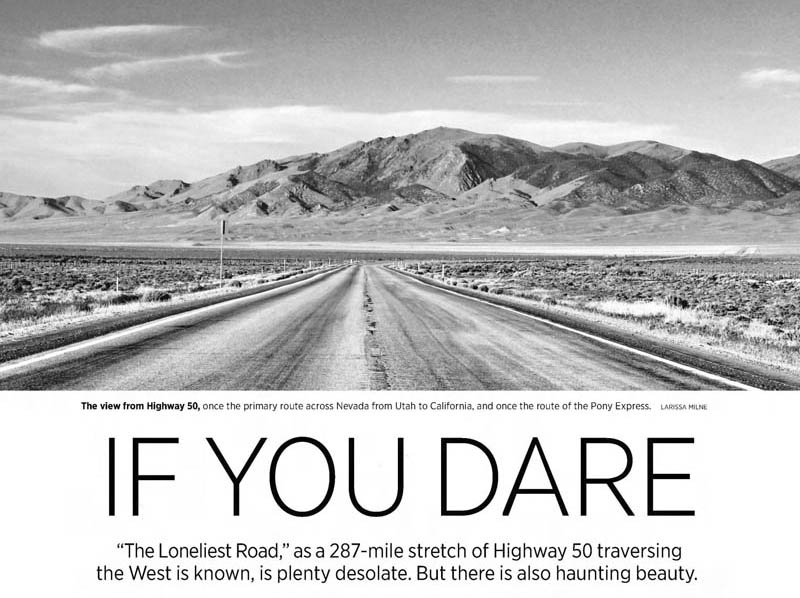

Introduction: The Loneliest Road

“It’s totally empty. There are no points of interest. We don’t recommend it… We warn all motorists not to drive there, unless they’re confident of their survival skills.”

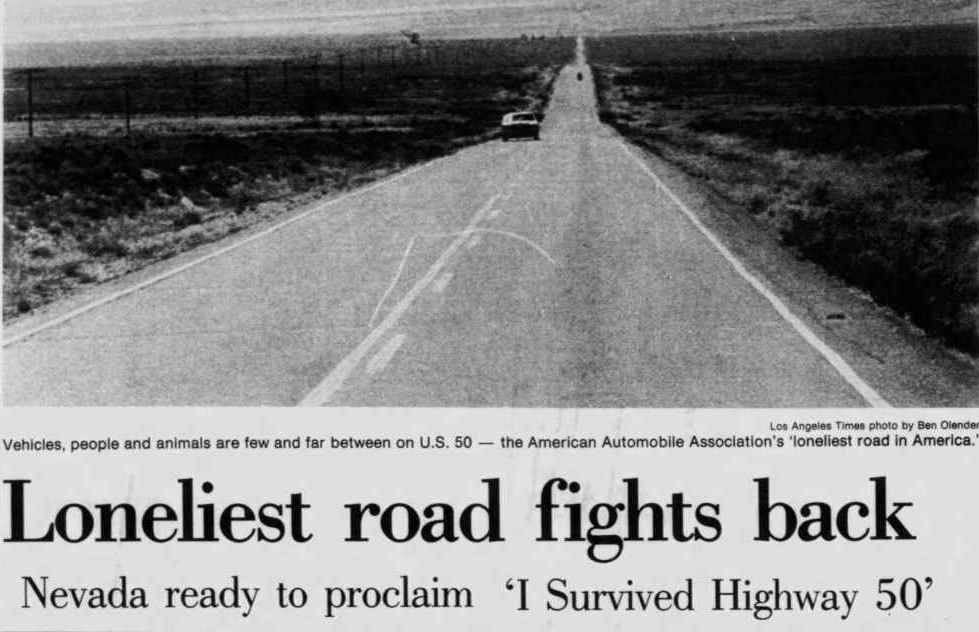

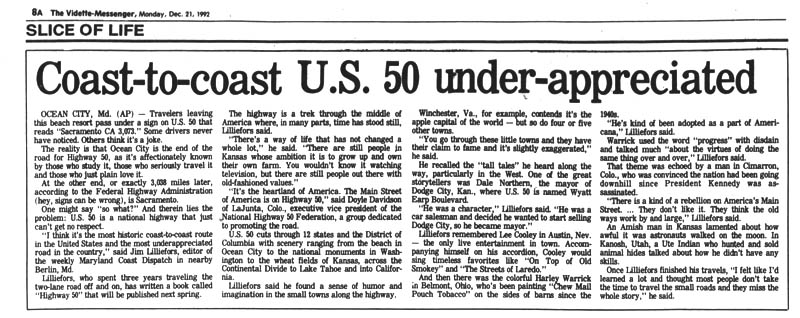

This American Automobile Association description, under the heading “The Loneliest Road,” appeared in a 1986 issue of Life magazine, referencing U.S. Highway 50’s course through the State of Nevada. Many residents along the highway’s 3,073-mile route took consternation from the phrase, recalling the transcontinental highway had once been a contender for the “Main Street of America.” The State of Nevada, on the other hand, saw the highway’s new-found infamy as an opportunity; less than a year later, the state legislature took ownership of the “Loneliest Road” moniker and began signing the highway as such. The Life magazine blurb erupted a war of letters in newspapers from Tallahassee to Boston to San Bernardino, each weighing in on the nearly-forgotten highway. The road’s newfound status as an issue of national concern was substantial enough to bring with it a public debate on the creation of nearby Great Basin National Park, approved by Congress just three months later.

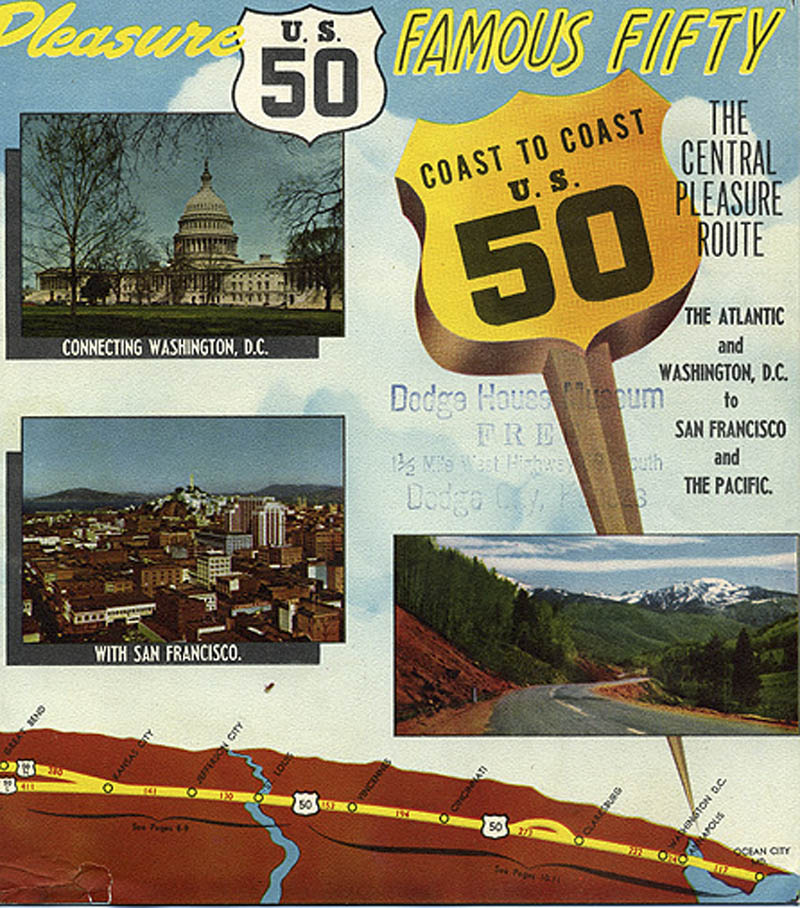

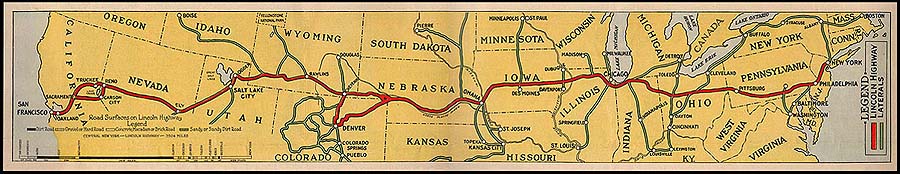

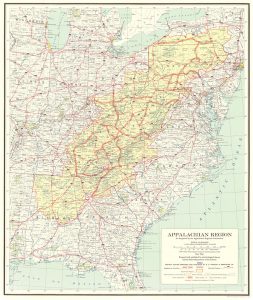

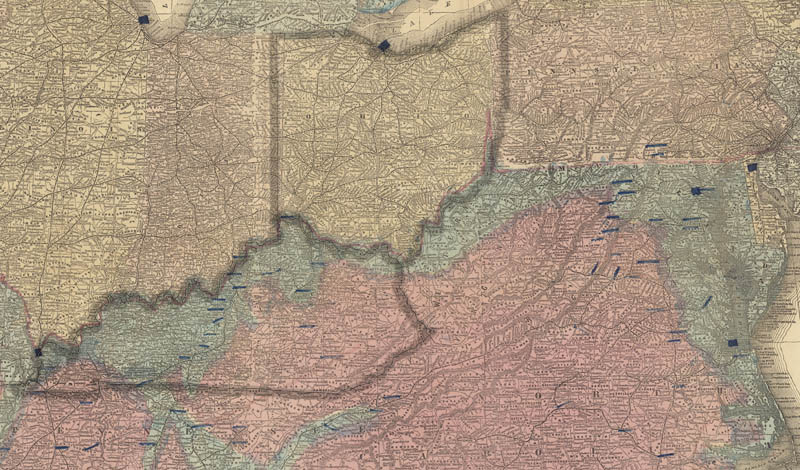

The course of Highway 50 coincides very closely with the geographic center of the conterminous United States. The highway encounters a significant diversity of subcultures along its path, making it a useful vector for analyzing American cultural history. Highway 50 winds from the cities of Washington, D.C., Cincinnati, St. Louis, Kansas City, and Sacramento, to the remote mountains of the West Virginia Appalachians and Colorado’s Rockies, to the vast farming country of the Midwest and Ohio River Valley, and ultimately through the now-legendary loneliness of Nevada and Utah’s Great Basin Desert.

The formal designation of Highway 50 with the passage of the 1926 United States Numbered Highway act is a convenient point of historical origin for the route, but the exact date of the route’s creation is a more complicated question. Some of the highway’s various passages follow old traces tracking back to prehistoric game trails, while others are presently rerouting as new construction in places where no path has ever laid. Here, we view the road in all its manifestations, regarding it from the several historic routes formally named Highway 50, as well as the old traces, trails, railbeds and even game trails the highway was routed along.

To understand the impact Highway 50 had on culture along its route, first consider what the United States looked like at the turn of the 20th century before the Numbered Highway System existed: Other than walking, horses were the primary mode of transportation in both city and country. The transcontinental rail routes completed a few decades earlier allowed for transporting people and goods throughout the frontier west, but their fixed routes presented significant geographic limitations. Long-distance transportation was still a rare, generally once-in-a-lifetime event, and usually undertaken via navigable waterways.

Passenger vehicles were a very rare site, held by a small, wealthy cadre of urban enthusiasts keeping ahead of the masses who had recently embraced a global bicycle craze. Paved roads were also a rare site, confined almost entirely to cities, and built at the behest of bicyclists. The turn of the century quickly fueled a new craze for automobiles, rapidly supplanting bicycling as the en vogue assertion of individuality and freedom for those who could afford them. By 1915, the recently-formed National Highway Association began a mass media campaign for “Good Roads Everywhere,” with their bronze icons of an eagle carrying the globe in its talons becoming a common site on radiator caps nationwide. The association released vibrant, full-color maps revealing a vision of the United States that could be: a webbing of black and red highways connecting every city, while passing through green national forests, yellow reservations, and purple National Parks. Nationalism and manifest destiny were unambiguous themes throughout this campaign, maintaining lock-step with the national defense themes that dominated American culture during World War I. The superlative themes of these propaganda pieces were not out of line; the Federal Highway System they proposed would become the biggest public works project in human history.

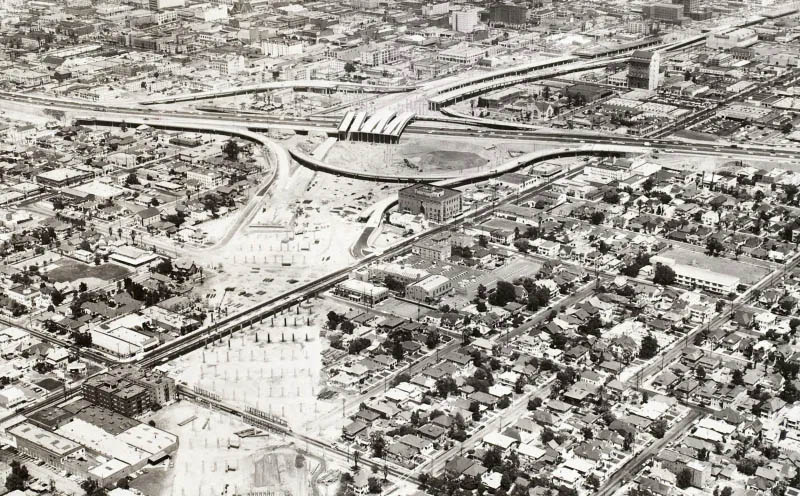

With the dawning of the Interstate expressway revolution of the late 1950’s, which was intent on replacing the then highly-congested Numbered Highway System, enthusiasm for Highway 50 as a contender for “America’s Main Street” began to fade. Debates over the value of the Interstate’s pioneering economy against its habit of bypassing small towns resulted in Highway 50’s corridor being almost entirely bypassed by the new Interstate Highway system. In the wake of this decision, small towns along the 50 endured, but did not thrive. Today Highway 50 remains, decades after the decommissioning of some of its more famous counterparts, a living museum of the culture left behind by the Interstate revolution. Owing to its geographic diversity, the highway also offers a useful cross-section of the evolution of American culture through its many historical intersections.

This digital museum is an exploration of the history along Highway 50’s cultural corridor, not only to understand the multitude of subcultures along the highway’s path, but also as a means of understanding the United States’ history as a whole, by treating the highway as an arbitrary and objective framework to explore the country’s broader historical patterns and relationships.

You can support this project directly through Buy Me A Coffee!

The Birth of U.S. Highway 50

The lame duck period of the American presidency, originally a four-month span between an election and the formal transfer of executive power, is largely a vestige of the poor condition and impassibility of colonial-era roads; it was expected to take as long for both news and electors to travel across the thirteen colonies. 1935’s Twentieth Amendment to the Constitution shortened the lame duck period by two months, emerging in an era when highways and the technologies following them progressively accelerated all aspects of American life, including politics.

The Good Roads Movement, beginning in the early 1880’s is the element most responsible for this acceleration. Despite the United States’ long-established reputation for poor-quality roads, this first organized movement to improve the nation’s roadways did not emerge until a bicycle craze swept the country during the 1880-90’s. The urban elites who popularized bicycling initially led the movement to build better roads for the sake of their own bicycles, not intending them for the rarely-seen automobile. The movement’s national newsletter, Good Roads Magazine, began publication in 1882 and demonstrated the effectiveness of the Good Roads movement’s influence through featured endorsements and articles written by prominent politicians and jurists, including future President William McKinley.

The movement’s early goals included securing federal involvement in funding public road improvement, as the federal government was the only entity with the financial means and impetus for common-good projects capable of financing such an expensive undertaking. Beginning in 1893, Congress created the Office of Road Inquiry, largely due to the efforts of bicycle manufacturer Albert Pope, whose personal fortune, vast connections, and flair for theatrics culminated in sending an over-sized petition of 150,000 names to Congress on two rotating spools tall enough to dwarf most people. Pope made charmingly compelling public arguments, such as his 1890 suggestion that the condition of the American road “probably gave rise to the theory of ‘survival of the fittest,’ because it would kill any ordinary mortal to ride over it.” By 1905, the Office of Road Inquiry confirmed the federal government would play a significant role in road construction, and adopted the more formal title of Office of Public Roads. The bureau endured three more name changes and a shuffling of positions in the Federal hierarchy until 1966 when its duties finally landed under the umbrella of the new Federal Highway Administration. Agency nomenclature was only a superficial reflection of the rapid pace at which systemic change occurred in the United States in this era.

The bicycle craze inspired the emergence of the first production-level motorcycles, which quickly evolved into automobiles. Wealthy bicycle enthusiasts rapidly embraced automobiles, and their early adoption of electric automobiles in particular made them a common sight on America’s city streets by the 1900’s. The ongoing successes of the Good Roads movement enabled further innovations in transportation; better roads for bicycles turned out to be just as good for automobiles. A nationwide explosion in highway improvement enabled city residents to freely explore beyond their city’s limits, shifting consumer desires towards vehicles with greater range. The limited battery capacity of the electrics of the era simply could not compete with quickly-refuelable internal combustion engines most commonly seen on rural farms. As consumer tastes in vehicles changed to emphasize the significantly longer-ranged internal combustion variety, electric vehicles quickly fell out of vogue for the rest of the century. The pleasure-touring urban gentry now adopted the noisy, hard-to-start, petroleum-powered internal combustion engines, previously a consort of the working farmer.

Rural Liberation

Highway 50 transects regions of extreme rurality and metropolitan centers alike on its path across America. Perceptions of an urban-rural divide between the two dispersive regions has always been an axiomatic aspect of American politics, from Thomas Jefferson’s 1803 description of cities as “the sinks of voluntary misery,” to Barack Obama’s 2008 rural dismissive “they get bitter, they cling to guns or religion or antipathy to people who aren’t like them… as a way to explain their frustrations.” The division has persistently defined national politics and shows no sign of fading from the public mind. Today, more than half of rural and urban residents respectively believe the other side of the divide holds completely different values from them. While America’s urban-rural division remains a popular target for political pundits to exaggerate differences between Americans, the cultural historical perspective shows this divide has rarely been narrower: Tracing the evolution of cultural values like freedom and nationalism on each side of the divide during the twentieth century reveals the United States Highway System as the prime instigating factor in drawing the two cultures closer together. Cultural values across the divide remain distinct today, but comparing that distiction to where it was a century ago demonstrates a dramatic narrowing. As American culture evolved with the highway network, the system effectively narrowed the cultural gap between rural and urban America by connecting the two at a human level. Suburban development, enabled by the highway system, best exemplifies the homogenization represented by this narrowing.

Ahead of the highway era, rural residents paid a material cost for foul road conditions in the form of broken wagon axles and losses in time spent between repair and extrication. Farmers largely regarded these losses a de facto regressive tax on their products. In 1918, the United States Department of Agriculture calculated the operating cost per ton-mile of corn, wheat and cotton transported by motor vehicle as costing half that of traditional wagon transport. The National Highway Association (One of several Good Roads organizations then in operation) highlighted these and other economic and social costs in a national mass-media campaign, printing and distributing an average of 14,000 pamphlets, maps, and bulletins each day of 1916, by its own accounting. The Good Roads movement’s propaganda coup seized on farmers’ ongoing frustration, and by the 1920’s most rural Americans had joined urban elites in enthusiastically supporting the national highway concept.

Other than walking, horses served as the most common means of transportation in the era before automobiles. For urban and rural travelers alike, equine feeding and upkeep proved a formidable expense, as animals needed to be fed daily, year round, whether ridden or not. In 1900, approximately one third of cropland in the United States was dedicated to growing hay for feeding horses. The burgeoning used car market following World War I proved automobiles a more cost-effective alternative to horses even before the creation of the first numbered highways. The 1920’s and 30’s progressed as an explosion of highway improvement and new construction nationwide.

Highways offered farmers expanded access to distant markets, while significantly decreasing expenses. The system also instigated infrastructure improvements following each new highway, offering easy maintenance access to utility lines along the network’s furthest reaches. The highways thus brought electrification to rural America, and along with it came radios, television, and eventually the internet, each beginning as a primarily urban phenomenon. These mediums increasingly exposed rural Americans to urban culture, as cities, holding the bulk of infrastructure and media talent, produced the majority of syndicated radio and television programming. The rapid expansion of access to radio newscasts contributed to a slow supplantation of the provincialism of rural America with a growing sense of nationalism. While broadcast media established a new national narrative, the highway system provided a tangible link to nationalist values such as manifest destiny. National identity was far more tangible for the hundreds of small towns along Highway 50, as the National Highway System connected each town’s Main Street directly to Washington, D.C.

By 1925, as improved roads began to reach deeper into rural America, motor vehicles transported 75 percent of California’s farm produce and 90 percent of Connecticut’s. Highways had the added benefit of allowing rural residents easy access to centralized education and medical care, once the sole province of urban life. Through increasing the mobility of labor, highways also brought farmers the freedom to continue farming in the face of an increasingly fickle labor market, particularly during the World Wars. Automobility also liberated farmers from complete dependence on human labor, as some farmers would remove the rear wheels from cars and trucks and replace them with farm implements to create improvised tractors. On the other hand, the same freedom enabling farmers to stay on their land also lured a younger generation towards the romance of distant cities. Restless youth, exposed to media depictions of cosmopolitan cities now a mere bus ride away, challenged the once-given intergenerational nature of farming. The population of rural America only slightly changed over the course of the twentieth century, very slowly increasing from 46 million people in 1900 to 62 million at the turn of the millennium. Urban and suburban communities represented the vast majority of population growth in the United States during this hundred-year period. While contributing to rural emigration towards cities, highways also brought urban diseases to the countryside; in the days before the development of motels or auto camping infrastructure, early auto campers driving from cities informally camped on the sides of roads. Their contribution of a sudden influx of roadside litter and human waste into local streams introduced minor epidemics of Typhus and other urban diseases otherwise uncommon in the countryside.

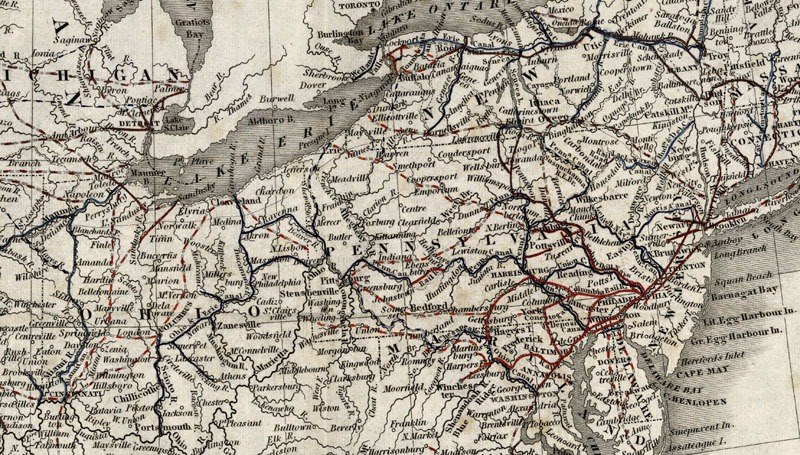

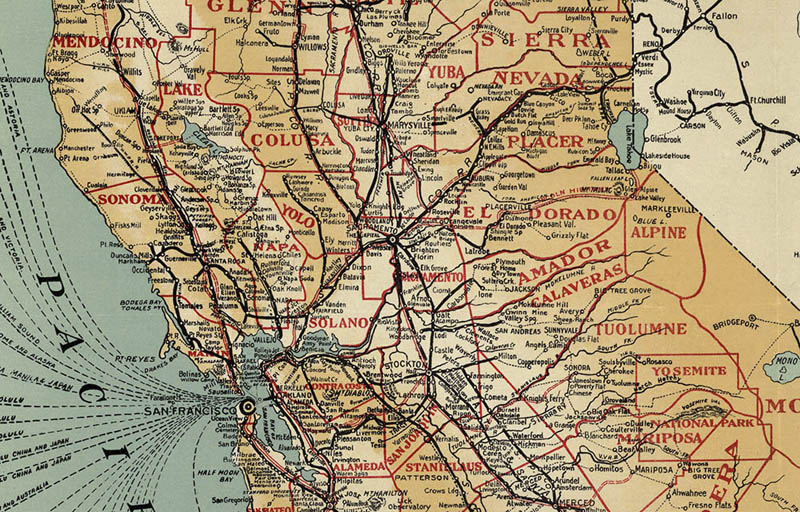

Maps and Legends

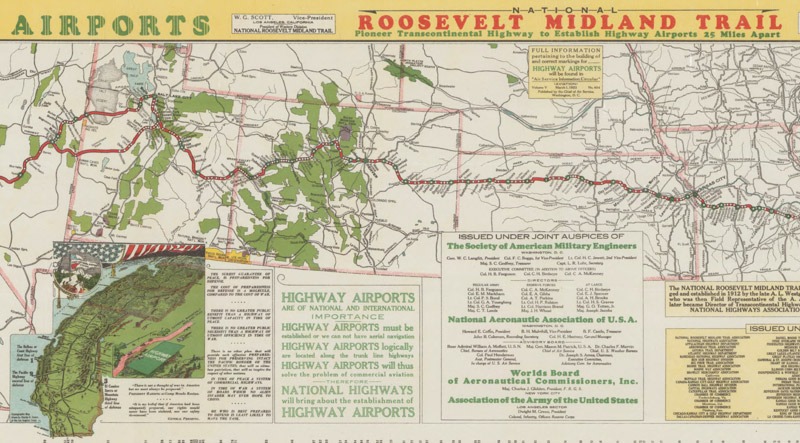

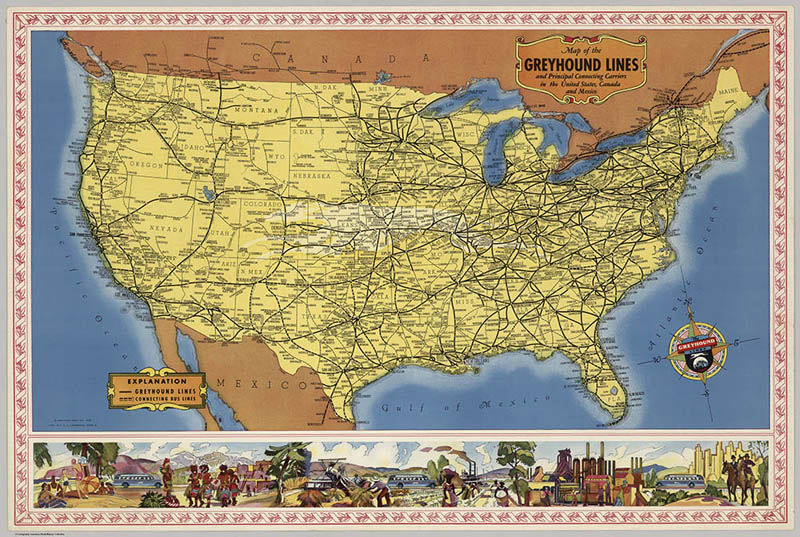

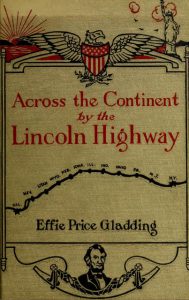

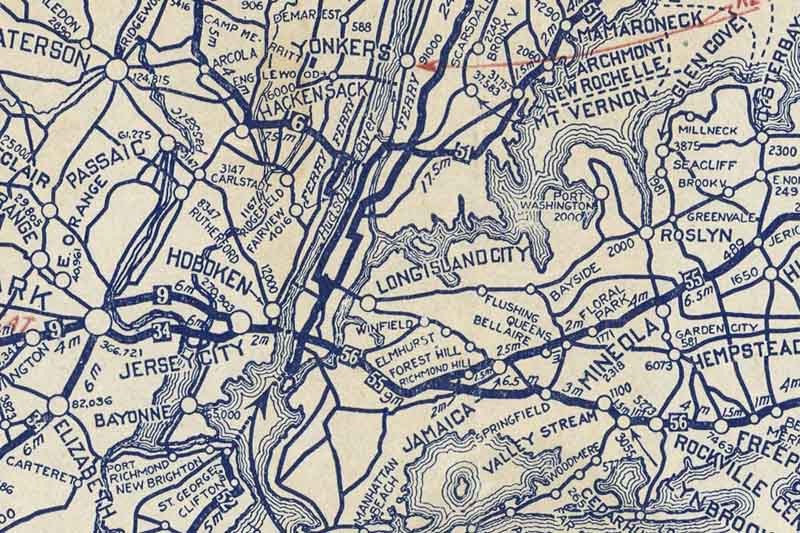

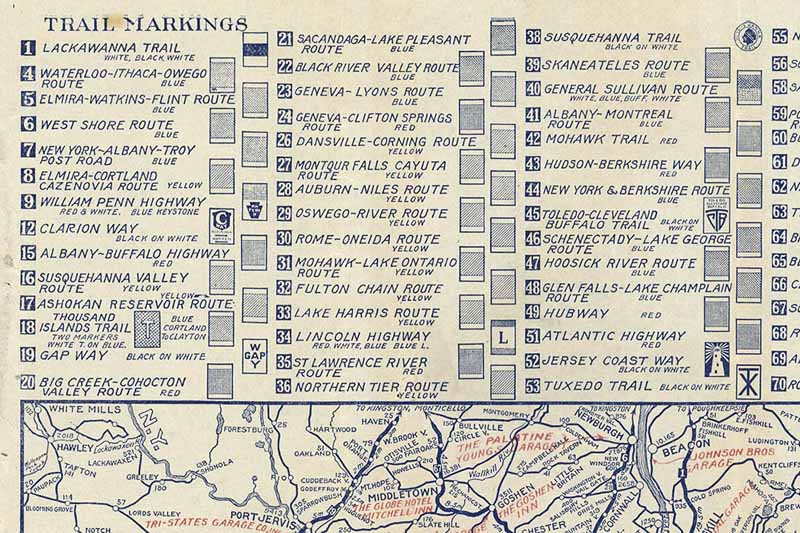

Before 1926, highways existed conceptually as independently-named auto trails, created and partially maintained by private organizations and routed along existing roads. Auto trail organizations produced signage and maps exclusively featuring their auto trail and the towns subscribing to their organization’s membership. At the dawn of the 1920’s, dozens of such named routes crossed America. Road maps at the time typically featured only a single route between two points and excluded other auto trails, as individual highway associations competed with one another. Dedicated in 1913, the Lincoln Highway was the first of these named auto trails to span from coast to coast. Predating the Numbered Highway System by more than a decade, 450 miles of the Lincoln Highway are shared in common with today’s Highway 50, from Ely, Nevada to Sacramento, California.

In 1917, John Brink, Rand McNally’s chief cartographer, somewhat accidentally invented numbered highways in an effort to construct maps featuring every named national trail in a given region. On maps of urban areas where multiple auto trails concentrated along the same route, Brink used numbers and a legend in order to save space. The numbered road idea quickly took hold with governmental highway planners, much to the chagrin of auto trail associations. With the creation of the United States Numbered Highway System in 1926, a numerical grid of urban expediency was now branded across the far reaches of rural America.

The Public Roads Bureau took a highly scientific approach to the issue of paving the national highways. The United States Department of Agriculture’s Experimental Farm in Arlington (along the road that later became Highway 50) undertook painstaking scientific tests on potential paving methods, exploring materials, subgrades, drainage, curing methods and bridge designs from 1918 through the 1920’s. Although the Federal Government has developed paving technologies and standards, its major contribution to the National Highway System has been through helping finance highway construction and maintenance performed by the states. Individual states each managed the overwhelming majority of highway construction and maintenance, the only true “federal highways” being those built by the federal government on federally-managed land such as National Parks. Although the federal government acted as a prime initiator in establishing Highway 50 along with the rest of the U.S. Numbered Highways, the seed of the cultural network that grew into the highway system took root generations before, and continued to evolve long after 1926.

Need to set up a website in a hurry? You can support the Digital Museum by patronizing our sponsors!

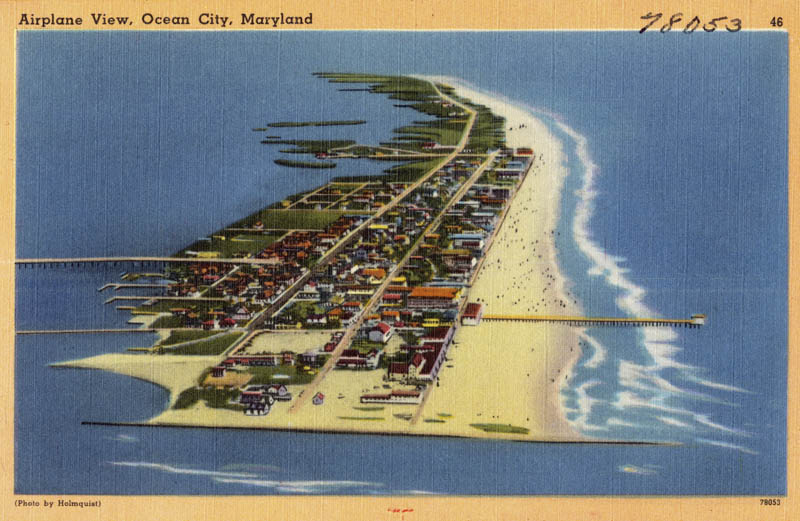

The Ladies Resort to the Ocean

From a geographic perspective, Highway 50 either begins or ends in Ocean City, Maryland, converse with its west-coast counterpart, Sacramento, California. In both cases, the highway’s termini have wandered over the years. The highway functionally terminated in Annapolis, Maryland until 1948, when the route took advantage of the 1942 construction of the Harry W. Kelly Memorial Bridge to open to an Atlantic coastal connection. On the west coast, the State of California used the 1936 construction of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge to extend the highway all the way to San Francisco until 1964, when a state-wide highway number realignment re-established 50’s Sacramento terminus as the extended route was redundant with other highways.

The resort promenade of Ocean City began as an isolated fishing village on the barrier spit of Fenwick Island, accessible only by stage coach and ferry. Opening its first motel in 1875, Ocean City’s remote nature allowed for a novel experiment in entrepreneurship for the era; by 1926 women owned or operated most of the city’s businesses including two thirds of the island’s resort hotels. Billing itself as the “ladies resort to the ocean,” Ocean City’s natural setting made it a desirable respite for tourists willing to make the trek from an increasingly urbanized Eastern Seaboard.

As the highway network expanded, the addition of the massive Chesapeake Bay Bridge in 1952 and Highway 50’s subsequent routing across it led to Ocean City’s “discovery” by residents of nearby Baltimore and Washington D.C. The gross influx of urban tourists quickly diluted Ocean City’s remote character in a sea of familiar franchise uniformity. Ocean City’s main thoroughfare, once largely the domain of independent women entrepreneurs, is today populated by a laundry list of corporate homogeneity: Dunkin’ Donuts, Cinnabon, Starbucks, Econo Lodge, and Hooters on the Boardwalk.

Learn more about Ocean City’s history at the Ocean City Lifesaver’s Museum.

The Greenbelt Experiment – America’s First Modern Suburb

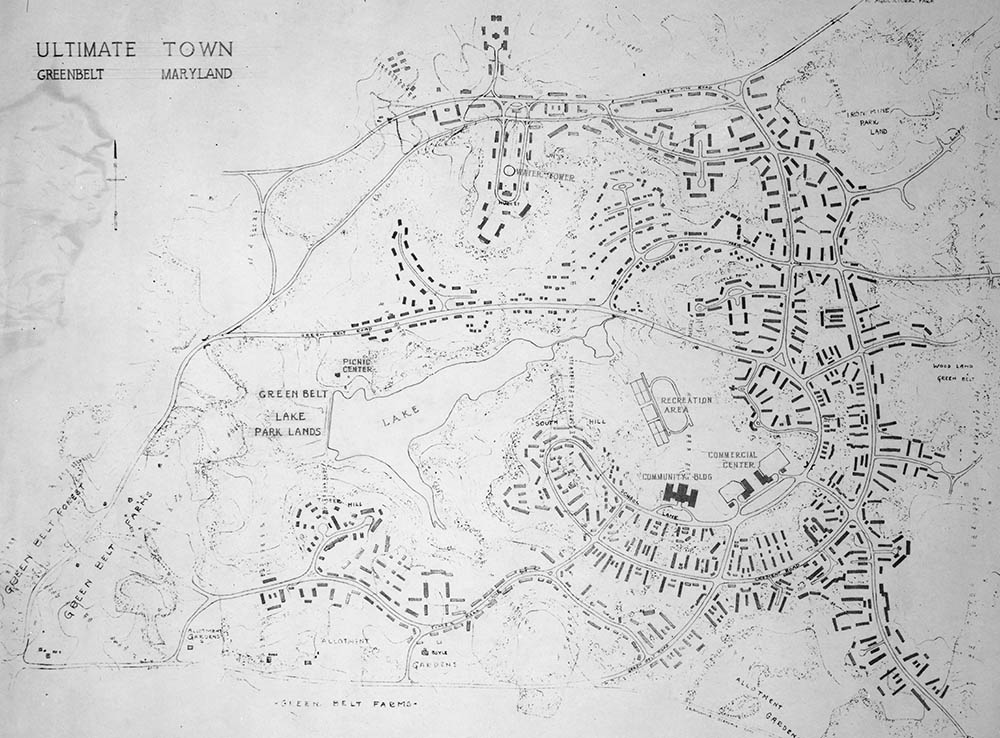

Pushing east across the Potomac Basin, just before reaching Washington D.C., Highway 50 brushes past Greenbelt, Maryland, one of three original Greenbelt project towns instituted by the New Deal’s Federal Resettlement Agency. Initiated as Maryland Special Project #1, the 1935 federally-planned and developed suburb, a social engineering experiment, became the primary template of private suburban development for decades to come. Conceived as a collectivist utopia by Undersecretary of Agriculture Rexford Tugwell, whose methods earned him the nickname “Rex the Red” among his critics, the government planned these colonies from a top-down approach in an effort to overcome the urban experience’s growing economic and psychic despair.

1939 – “The City” documentary contrasts urban life to the planned suburb of Greenbelt, MD

Greenbelt employed the concept of landscape and architecture as a means of social engineering, a process pioneered in the 1920’s by the Regional Planning Association of America. The road system within Greenbelt focused on auto-commuting and safety, featuring three-way intersections, cul-de-sacs, and pedestrian undercrossings. The citizens of Greenbelt formed several co-ops, communally organizing a credit union, supermarket, and gas station during Greenbelt’s first few years. In the Greenbelt model, urban planners saw the highway’s potential for settlement decentralization decades before the Interstate Highway System patented the process. Increased automobility allowed for longer commutes between home and work while eschewing the need for public transit infrastructure. Rural land proximate to cities could be purchased wholesale, subdivided into affordable individual lots, and sold to families seeking to escape congested and polluted cities. The utopian visions inspired by the Greenbelt model promoted suburban dreams, albeit not according to morally-agnostic platforms; future developers, real estate agencies, and banks applied racially discriminatory policies in determining who would participate in these dreams.

During the second Red Scare of the 1950’s, the collectivist-inspired Greenbelt towns came under suspicion of socialist influence, later falling prey to private development efforts following a real estate boom in the wake of nearby expressway expansion. Despite being considered a policy failure by many, the Greenbelt experiment profoundly influenced the private market’s future dominant landscape of American residential development, the suburb. Despite suburbia’s well-earned reputation for unsustainability, sprawl, dependency on fossil fuels, and role as an unnatural extension of racial housing biases of the 1950’s, individuals from both urban and rural areas are today united in their desire (over 50 percent in both cases) to relocate to the suburbs, maintaining a decades-long trend.

The Greenbelt experiment was just one of a litany of New Deal projects involving the National Highway System. The Great Depression and concurrent Dust Bowl of the 1930’s saw millions of Americans displaced by perilous financial and environmental conditions. Unlike earlier depressions and recessions, the highway system allowed common Americans of the 1930’s unprecedented freedom to migrate out of their economic circumstances. Millions of rural residents migrated into cities in this era, a process famously depicted in John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, while the Works Progress Administration (WPA) brought millions of workers out of urban breadlines and into small towns and federal lands to build base infrastructure, schools, libraries, armories, and roads throughout the United States. Between 1935-43, the WPA built or reconstructed 651,087 miles of roads, 88 percent of which were classified as rural.

The WPA also employed writers who journeyed across the United States authoring travel guidebooks highlighting American culture. Each book was written according to a government-issued style guide and defined the national imagination for thousands of future tourists.

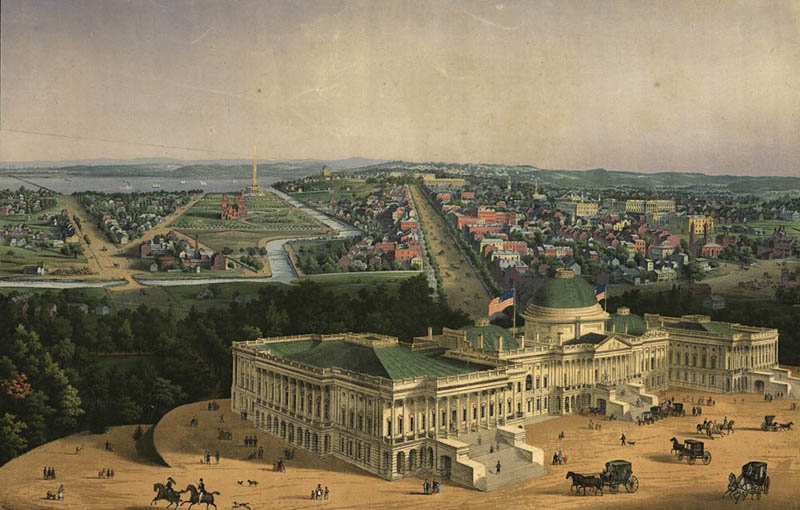

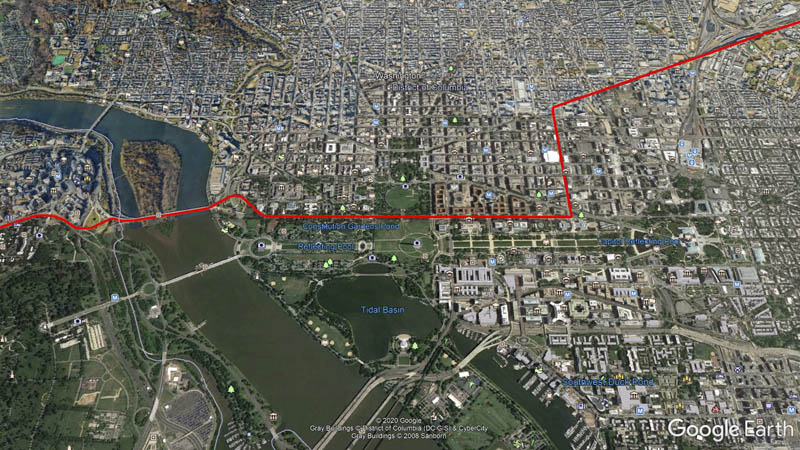

The Zero Milestone

In nearby Washington, D.C. proper, Highway 50, along with its longitudinal counterpart Highway 1, share the honor of lining the National Mall between the United States Capital and Lincoln Memorial. Highway 50’s present routing through the heart of the federal district follows the main thoroughfare of Constitution Avenue, passing icons such as the Smithsonian Institute, the Washington Monument, the White House, the World War II memorial, the Vietnam Veteran’s Memorial, and the Lincoln Memorial, before departing over the Theodore Roosevelt Bridge into Arlington Virginia. Before the turn of the 1890’s, Constitution Avenue’s course was the Washington Canal, a diversion of Tiber Creek, and the land now occupied by some of the United States’ most hallowed monuments was all beneath the Potomac River.

A slow land fill process created this area, pushing south and westward from the footing of the Washington Monument beginning around the middle of the 19th Century. The process largely completed in anticipation of the 1892 Worlds Fair on the grounds, which ultimately was never held. The area underwent major changes over the subsequent decades, featuring botanical greenhouses, groves of elm trees, and massive rows of military office buildings during the World Wars, before ultimately landing as a permanent memorial park. It is historical irony that the area hearkening to America’s most entrenched traditions has been a place of near perpetual evolution, continuing to this day.

The Zero Milestone, a granite marker laid by the Good Roads Movement in 1923 to commemorate the launch of the first cross-county automotive military convoy four years earlier, rests along Highway 50’s course near the center of the Ellipse, the large lawn in front of the White House, just a block north of Highway 50. Although the milestone’s construction sparked a brief fad of other cities across the country founding their own milestones in the style of ancient Rome, it never came to serious use as a gauge for highway distances and today remains a curiosity occasionally targeted by the National Park Service for removal.

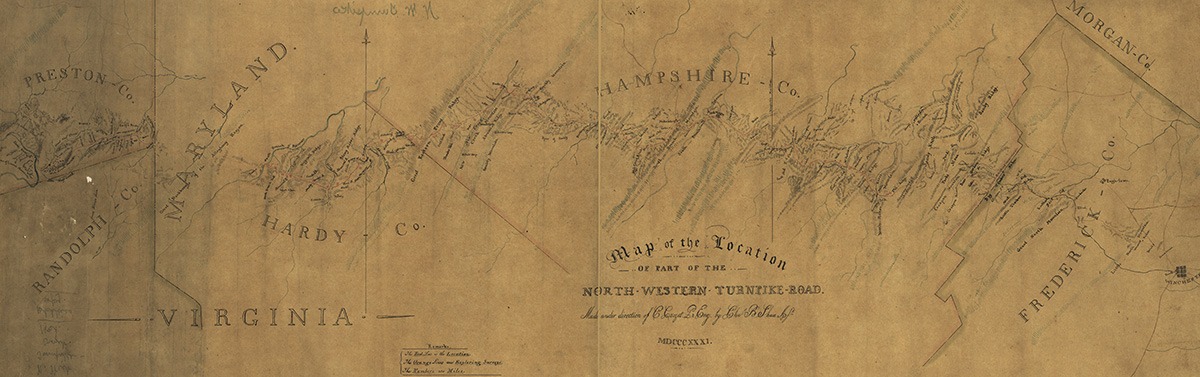

Opening Appalachia

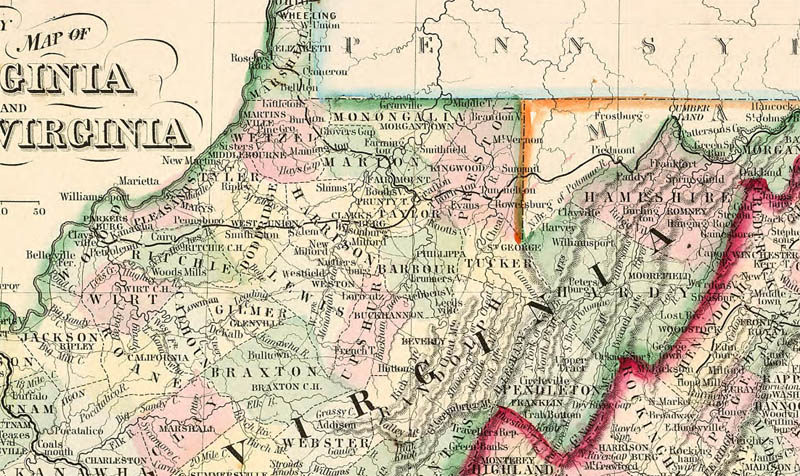

Highway 50’s route from the Potomac basin into Appalachia follows the course of one of America’s oldest formal wilderness roads, the Northwest Turnpike. Following a rare east-west trace transecting the meridional Appalachian mountain range from Fredericksburg, Maryland to the Ohio River, from its earliest days the road acted as a pipeline between Northern cities and the frontier Trans-Appalachian west. The region’s overall geographic impenetrability guaranteed the endurance of its hyper-rural character for generations. Engineered highways of the twentieth century, able to traverse rugged terrain, ultimately overcame the Appalachian’s natural barriers otherwise impossible for rails or canals to breach. The north-south orientation of Appalachian ranges and valleys eased migration from Pennsylvania and the north compared to frontal approaches from the east, while the land’s rugged nature rendered cash-crop plantation economies untenable; both factors influenced the region’s political distinctiveness, combining with the land’s remote character to produce a unique cultural amalgamation.

The culturally distinct nature and provincialism of the region led to its consideration as a wholly separate colony years before the United States Constitutional Convention. Residents of the region proposed partitioning the frontier mountains as a fourteenth British colony, Vandalia, in the mid-eighteenth century. Following the Revolutionary War, a likewise movement called for a fourteenth state called Westsylvania; both movements roughly covered today’s West Virginia, and were met with significant opposition from their respective governments. West Virginia ultimately gained its status as an independent state when it seceded from the Confederacy to join the Union during the height of the Civil War.

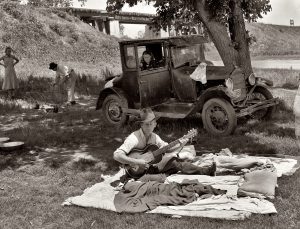

Federal and local efforts improved roads into far reaches of Appalachia, opening doors for cultural exchange with the once-isolated hillbilly culture that thrived in the region despite generations of hardship. The new highway system thereby enabled one of the most significant episodes in American music history. In 1933, Library of Congress folklorist Alan Lomax began driving his Plymouth, outfitted with a portable recording studio, into the depths of rural America to collect its musical heritage, forever changing the course of American music. While focusing on the Appalachians, Lomax’s musical odyssey took him to dozens of remote enclaves from southern Florida to Michigan’s upper peninsula until his car was “literally falling to pieces.” Lomax’s on-the-road “discoveries” of Muddy Waters, Woody Guthrie, Lead Belly, and Pete Seeger, to name a few, brought American folk and blues music to generations of people far removed from their rural origins. The Lomax recordings sowed seeds nationwide of the musical genres hillbilly and race, which later evolved into country and R&B. Lomax made recordings in at least eight locations along Highway 50.

Despite its nationally-recognized cultural contributions, Appalachia’s sparse population and rugged geography presented significant economic challenges for the region. Pursuant to President Johnson’s 1960’s “Great Society” initiatives, the Appalachian Development Commission’s Highway System designated Highway 50’s course from Harrison, West Virginia to Athens, Ohio Corridor D, allocating federal funds to highways in this region largely avoided by the Interstate system for its engineering challenges. The program created 21.8 billion dollars of additional income for the Appalachian region in the subsequent fifty years, increasing annual per-capita incomes by almost $600, while generating 31.7 billion dollars for outside regions. The program economically enriched Appalachia, as trade with outside cities proved increasingly lucrative for both sides of the divide.

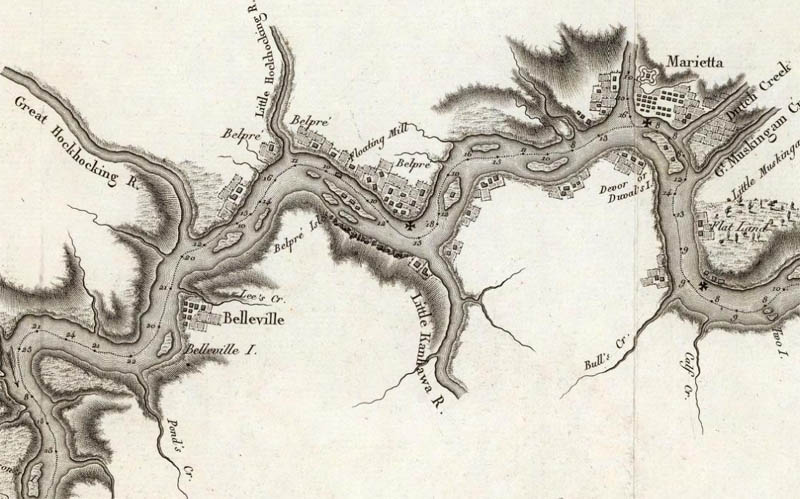

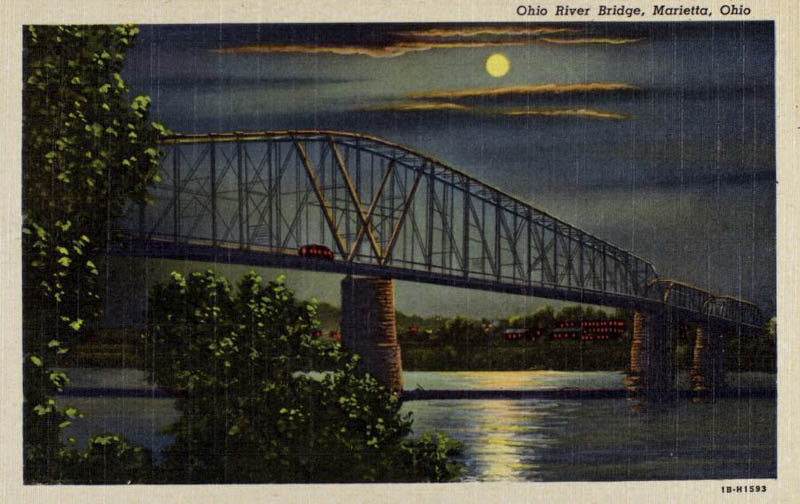

Ohio River Valley

As Highway 50 descends from the Appalachians into the Ohio River Valley, its course straightens to interconnect a series of small historic cities on its course to Cincinnati. The highway’s routing through Ohio was most influenced by the Land Ordinance of 1785 and the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, the former setting aside one section of each township in the Northwest Territory (roughly today’s Great Lakes states) for the support of public schools. The latter advanced establishment of public education as a political mandate in the Northwest Territory. Ohio, the first such state carved from the new territory, began work on Ohio University along a far reach of the Hocking River in the late 1700’s. The university’s location was selected for its placement halfway between Chillicothe, the territorial and future temporary state capital, and Marietta, the territory’s first permanent settlement. Shortly after the founding of the university, the village of Athens grew around it, eventually forming a small city in the midst of the rural western Appalachian foothills.

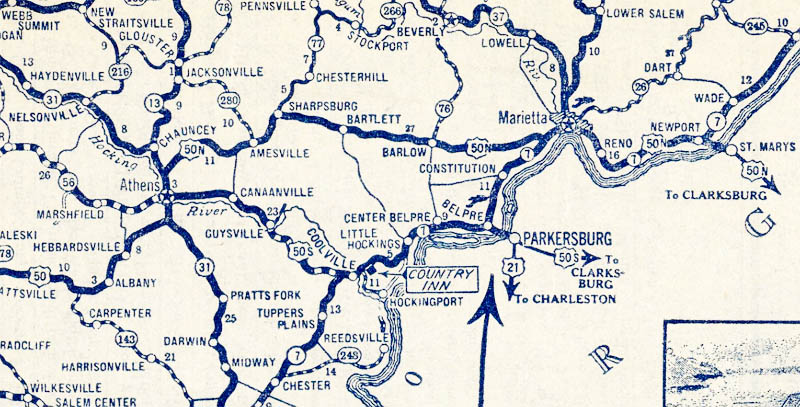

The American settlement pattern of the territory in this era largely confined itself to navigable rivers, whereby trade was centered in distant New Orleans. Native pathways and game trails comprised almost all overland travel routes at the time of the university’s 1804 founding. Highway 50’s route followed the tracks of the Marietta and Ohio Railroad, a direct link between the three towns of Marietta, Athens, and Chillicothe. The leg of U.S. 50 between Athens and Marietta was originally a split route, 50N, whose counterpart 50S connecting Athens to Parkersburg, West Virginia ultimately won the unified U.S. 50 designation. A historical echo of a nineteenth century railroad controversy initially split the route, whereas the Marietta and Ohio Railroad had been originally chartered as the Belpre Ohio Railroad and re-routed following the machinations of the Marietta business community. The State of Ohio decommissioned 50N in 1976, and rechristened the road as Ohio State Route 550, a locally-popular scenic alternative to this day. Most of the remainder of 50’s route across Ohio was solidified during the New Deal, when the Civilian Conservation Corps improved much of its road between Athens and Cincinnati, including Cincinnati’s Columbia Parkway.

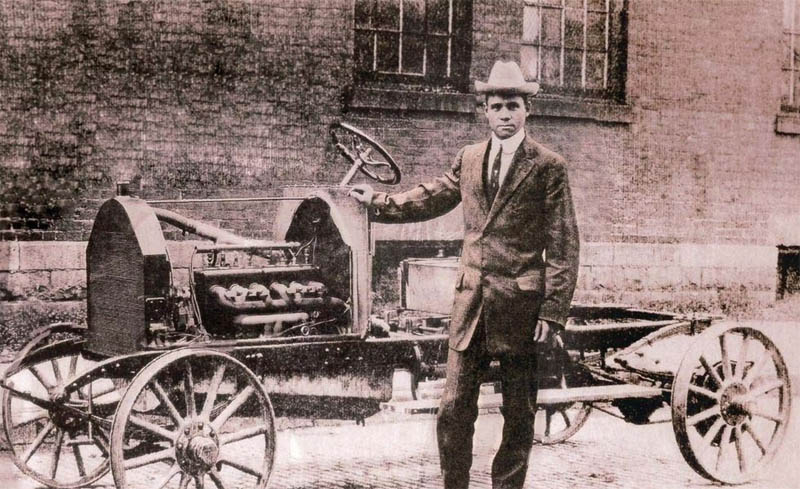

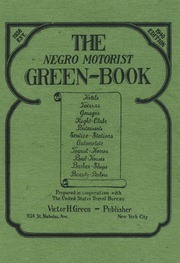

C.R. Patterson and Sons

Compared to earlier transportation models of rivers, canals, and railroads, the highway system democratized access to travel and migration. The highway experience for black Americans, however, was marked by challenges not experienced by white travelers. The 1920’s saw an explosion in Ku Klux Klan memberships, and hundreds of rural “sundown towns,” including many along Highway 50, embraced the exclusion of blacks after sunset. Freedom to travel does not imply security in doing so; the vulnerability accompanying the isolation of rural highways inhibited leisure travel for many black Americans in the 20th century. Corrective measures, including Victor Green’s publication of The Negro Motorist’s Green Book, a guide to black-friendly traveler services across the country, took much of the guesswork out of avoiding awkward and often dangerous situations for motorists. The Green Book celebrated the highway as a venue for expanding black liberation in America. An article by trade school president Benjamin Thomas in the 1938 edition highlighted the economic advantages the automotive boom offered blacks to escape the service class into the mechanical middle class. Thomas touted entry-level automotive work, as both a chauffeur’s or mechanic’s starting wages earned three-times the typical service wages of black Americans at the time.

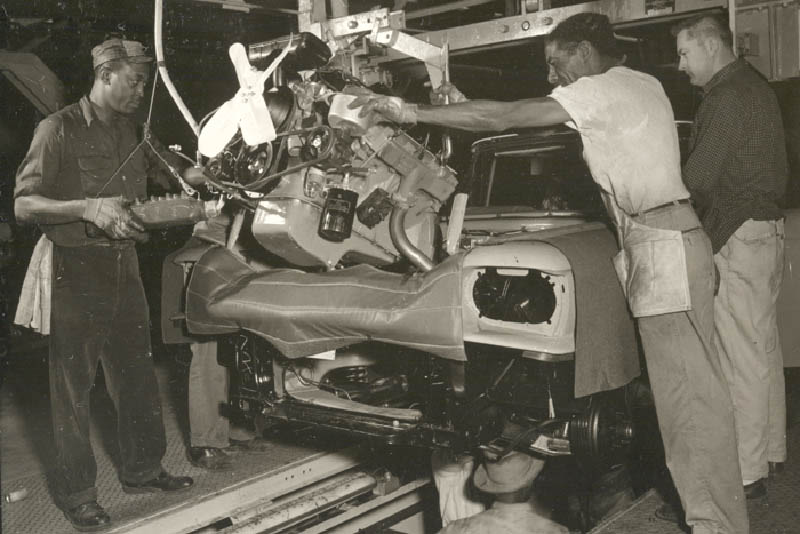

The Great Migration of roughly six million black Americans from the rural South into Northern cities through the mid-twentieth century maximized the highway system’s ability to empower individual self-determination in the face of brutal circumstances. While offering freedom from oppression in the South, the Great Migration also enabled the freedom to pursue economic opportunities provided by the automotive manufacturing cities of the North. Although black employment in the industry was still scant at the time of Thomas’ writing, the era during and after World War II saw a steady increase in black employment in the auto industry, as Detroit experienced a twenty-fold increase in its black population between 1910 and 1930.

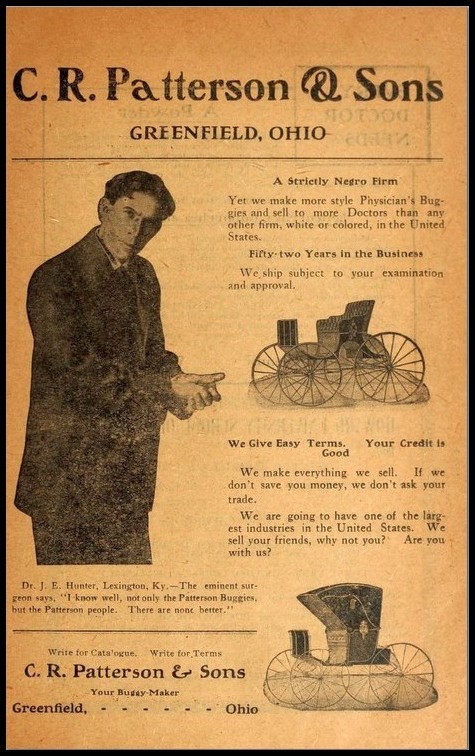

The early hostility of the manufacturing industry towards black employment did not prevent individuals from innovating their own industry; far away from the urban industrial centers of the Great Lakes, ten miles north of Highway 50, the rural town of Greenfield, Ohio, hosted America’s first (and only) black-owned and operated automobile manufacturer. C.R. Patterson & Sons, co-founded by a former slave, began manufacturing traditional carriages in 1865. Under the leadership of Patterson’s son, Frederick Douglas Patterson, the company adapted to automobile manufacturing, becoming the largest of such in the state of Ohio. Frederick Douglas Patterson (Not to be confused with the founder of the United Negro College Fund by the same name) was a man of considerable first accomplishments. Only able to attend the local white high school after his parents sued the school district, he arrived as their first black student and graduated as their first black valedictorian. He went on to become the first black football player at Ohio State University as well as class president in 1893. He was a contemporary of Booker T. Washington as a member of the National Negro Business League, served as “Worshipful Master” at the Greenfield Freemason Lodge, and was a prominent member of the Ohio Republican Party.

The company eventually retooled for commuter bus fleets, providing early buses for the cities of Cincinnati and Cleveland. Unfortunately for Patterson, the freedom to access urban markets worked in both directions; the highway system put small companies in direct competition with the emerging urban assembly lines of the 1920’s powerhouse of Detroit. Even while producing 400-600 vehicles per year, C.R. Patterson & Sons, like most small auto manufacturers, could not compete with the assembly line production of mass-market vehicles. Coupled with losses during the great depression, C.R. Patterson & Sons closed shop in 1939 after 74 years in business.

Manufacturing jobs were not the only avenue by which black Americans made economic gains in the automobility network. By 1940, blacks owned more than a third of Esso (today’s ExxonMobil) service station franchises, and the company was a leader in distributing Green Books through its stations. While the examples of C.R. Patterson & Sons and Esso demonstrate the possibilities available to some black Americans in this era, these outcomes were far from typical.

Hillbilly and Race in the Queen City

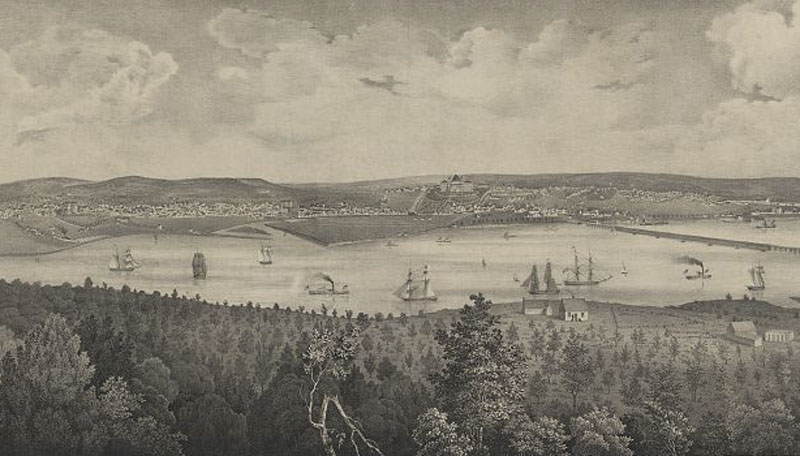

The next city Highway 50 meets heading westward is Cincinnati, Ohio, coined “the queen city” for its sublime features since at least 1819. Highway 50’s course through Cincinnati mostly clings to the serpentine banks of the Ohio River, one of the oldest, longest, and largest rivers in the United States, which served as an early Interstate highway of its time, connecting the Ohio River Valley with the global economy by way of New Orleans. Cincinnati has always been a cultural crossroads due to its role as a transportation hub. Situated at the confluences of the Ohio River with the 300-mile long Licking River to the south and the 100-mile Little Miami River to the north, Cincinnati forged diverse cultural connections with the deep south, central Appalachia, industrial Pittsburgh, and the Midwest farm country of western Ohio. The canal-building decade of the 1820’s saw the completion of the Ohio-Erie Canal, The Erie Canal, and the Pennsylvania Canal System, all of which connected the Ohio River and Cincinnati to even wider markets including Canada and the Eastern Seaboard. The later arrival of railroads largely followed the ports of the existing river trading network, making Cincinnati an early railway hub as well.

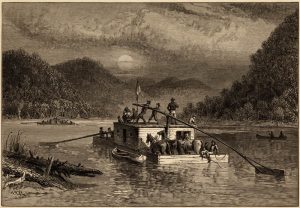

Before the invention of the steam boat, navigation of the Ohio River was typically a one-way river trek run by Kaintucks, flatboat rivermen who would load their rafts with agricultural goods and merchandise, float them down the Ohio and Mississippi rivers to New Orleans, sell their goods and the lumber from their flatboats, then walk another of the oldest roads in the United States, the 700-mile Natchez Trace, back to Kentucky. The experience foreshadowed America’s slow transition from river-based transportation networks to overland highway routes, but the highways had a long way to go to beat the relative ease and speed of river transport.

The Ohio River also served as the border between the Southern United States and the North; Cincinnati was on free soil, but 1,000 feet across the river in Kentucky, slavery remained legal until the 1865 passage of the 13th Amendment. This geographical situation, along with Cincinnati’s position as a transportation hub, made it a vital channel for the Underground Railroad, the clandestine organized effort to aide slaves escaping to the North. For most slaves seeking to escape the United States altogether, Ohio was the most direct route to reach Canada by way of Detroit. Cincinnati’s proximity to, and partial economic dependency on the Southern institution of slavery, contrasting with its strong abolitionist backbone, contributed to a long history of racial and political tension including a plague of semi-regular race riots throughout its history.

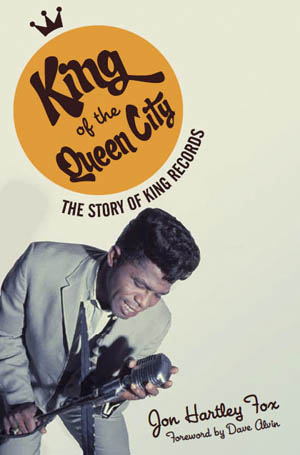

Cincinnati also provided a significant venue for cross-racial cultural collaboration. About a mile northwest of Highway 50’s course through Cincinnati lies a dilapidated brick warehouse which only recently escaped demolition. The building was once home to Syd Nathan’s King Records, originally a hillbilly music label, which along with its race music imprint Queen Records launched the careers of dozens of the most eminent popular musicians of the mid-twentieth century. The artistic network of King Records was a microcosm of the cultural refinery of the city of Cincinnati, a natural crossroads between the urban North and rural South on the banks of the Ohio River.

Hillbilly and race artists with both King and Queen Records collaborated with each other so often, Nathan merged the two in 1947. The King Records’ roster reads like a laundry list of the the twentieth century’s most influential recording artists, including its most famous alum James Brown. The company produced hundreds of records from the middle of World War II until 1971. Urban recording companies in the era King Records emerged from typically kept strict divisions across genres according to racial lines. King Record’s unique contribution as a new type of forum simultaneously promoted multiple genres like blues, rockabilly, and swing. The consistent interactions between hillbilly and race artists at King Records primed the American music scene for a new trend of hybridized genres, including rock and roll.

Outlaw Moonshiners vs. the Ku Klux Klan

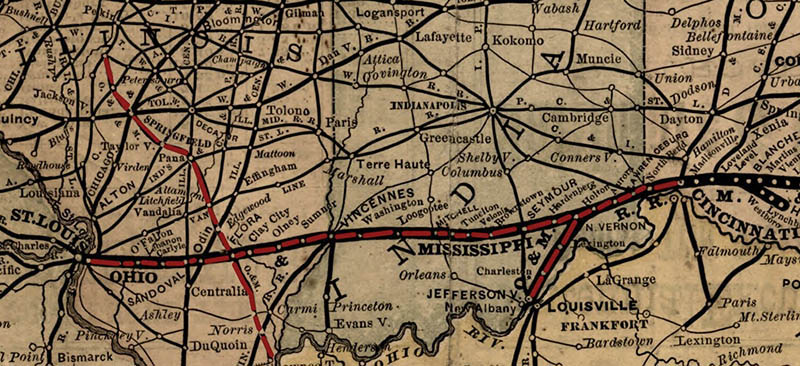

Highway 50 leaves Cincinnati along the course of the Ohio and Mississippi Railway, the westernmost branch of the eastern railroad network at the time of its creation in 1857. This passage of the O & M Railway through Indiana gained early infamy as the location of the first three peacetime train robberies in the United States, all of which were committed by the notorious Reno Brothers Gang of Jackson County between 1866 and 1867.

The American railroad network reached its zenith around the same time as the arrival of the U.S. Highway System. Early highway routing took advantage of existing railroad courses, which typically followed the most efficient engineered routes. Compared to the private railroad network’s often-arbitrary selection of station towns, the highway system offered spontaneous extensions into rural areas, allowing for economic development on a far more democratic scale. The modernization and rural reforms embodied in the highway system exemplified a triumph of the Progressive Era from which it emerged, permanently etching 1920’s progressive values onto the landscape of the United States.

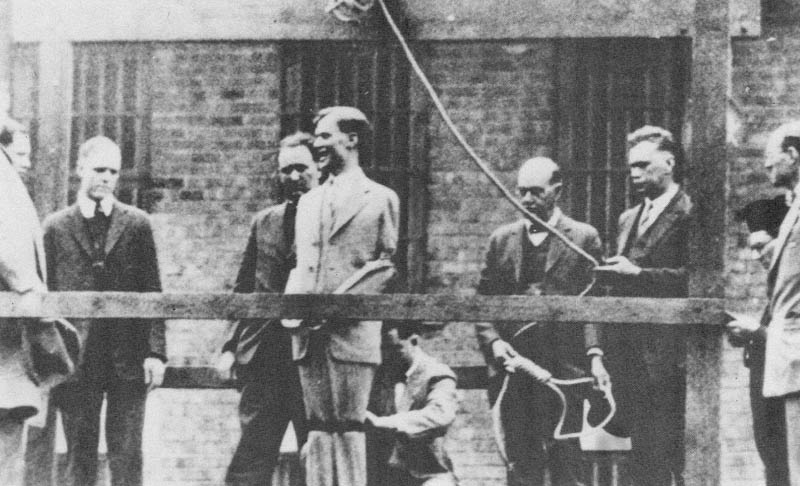

Progressivism, however, had its dark side. The 1920’s saw millions of white Americans casually joining the Ku Klux Klan as one of a litany of popular middle-class gentlemen’s clubs. The KKK embraced some of the Progressive Era’s most radical political policies, bolstered by then-popular racial science, eugenics, an honor-based platform for the advancement of women, and an absolutist pro-temperance stance. The resurgence of the decades-long defunct KKK appealed to would-be Klan members intimidated by both black Americans’ migration into Northern cities, as well as increasing numbers of foreign immigrants into the United States. The Klan’s 1920’s incarnation was popular in midwestern urban areas compared to its first manifestation, with roughly half of its members living in cities between 1915-1944. Its hardline pro-temperance stance put its rural branches in direct confrontation with cottage-industry moonshiners. In 1926, Highway 50 arrived in the region of Southern Illinois finding the area gripped by violent regional conflict between rival moonshining gangs and the KKK. Criminal gangs controlled the moonshine industry, regularly fighting each other in increasingly deadly skirmishes. With the arrival of the Klan, two of the dominant criminal rivals in the area, Charlie Birger and the Shelton Brothers Gang, briefly united against their common enemy, routing the KKK in Southern Illinois and permanently diminishing its influence in the region.

Highway 50 served as an informal divide between southern Illinois’ bootlegging region, and the north, where all roads led to Chicago’s bottomless moonshine market. Illinois’ bootlegging network fit well within the automobility framework, using highways as an economic pipeline from countryside sources of moonshine production into cities, the major consumers of illicit spirits. Speed, as a value of automobility, saw network-wide gains in this era, borne from the necessity of rum runners, members of the moonshine transportation network, to convey their illegal cargo as quickly and inconspicuously as possible. Rum runners stripped their vehicles of all but the absolute necessities to keep up the appearance of normalcy in the eyes of law enforcement while simultaneously reducing weight to keep the heavily-laden autos moving at maximum velocity. This process became a competitive field for the rum runners, resulting in the birth of the stock car racing subculture, an initially rural phenomenon which quickly spread nationwide. Moonshining and stock car racing subcultures firmly established themselves, such that both survived the passage of the Twenty-First Amendment and subsequent end of prohibition. The 1948-founded National Association of Stock Car Auto Racing (NASCAR) emerged directly from this subculture and celebrates the automobility values of speed, freedom, and independence to this day. Remaining true to its rural roots, NASCAR continued to race on red-clay dirt tracks for its first three years before paving its tracks.

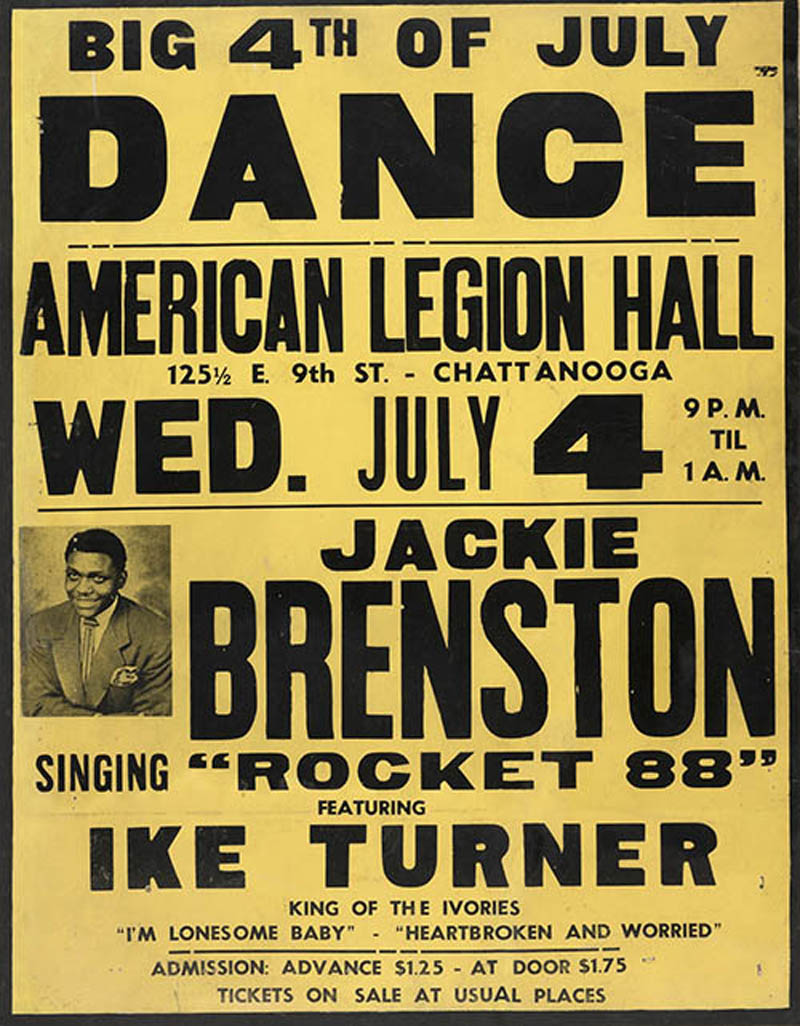

NASCAR’s homologation process, requiring all competing vehicles to be based on stock cars available for sale to the public, resonated on the consumer auto market; racing performance became a venue by which consumers judged vehicles, and auto makers responded by increasing engine horsepower well beyond the range of consumer’s earlier utilitarian needs. In 1949, a year after the creation of NASCAR, Oldsmobile released its Rocket 88, the first consumer-edition muscle car, inaugurating a decades-long fad. Ike Turner and Jackie Brenston’s 1951 car song by the same name is considered one of the first rock and roll songs. (Controversially the first, by many music scholars) The hybridized genre of Rock and Roll music reunified the styles of country and R&B following their decades-long racially segregated tours of the urban sphere, and was a direct product of the highway’s network of automobility.

The Real McCoy

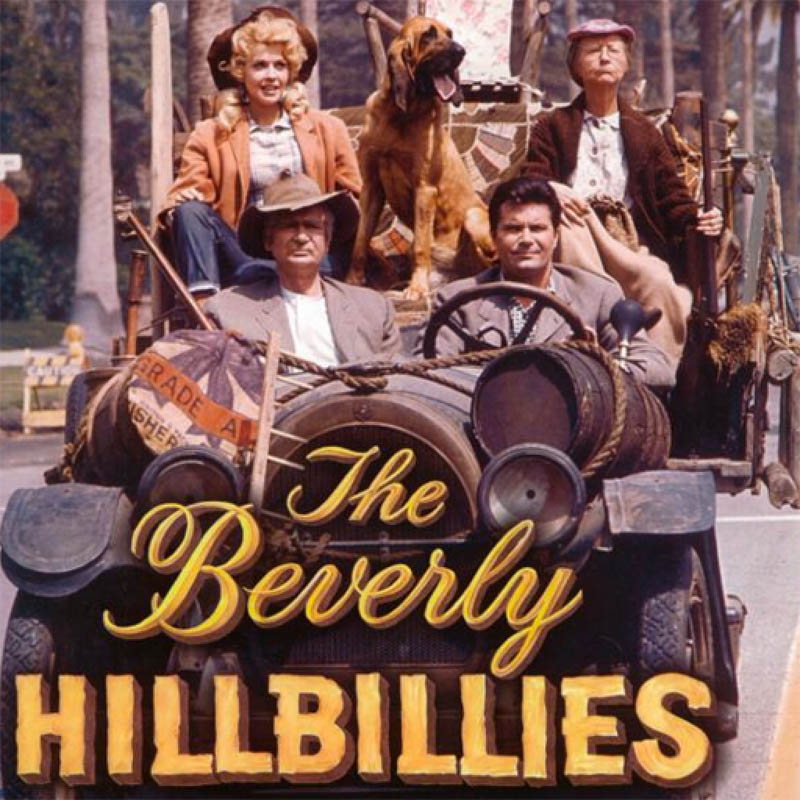

Music was only one of many narrative art forms shaped by the highway network. The efforts of one writer, Paul Henning, shaped much of the national imagination of rural life during the 1960’s. Growing up a few miles north of Highway 50 in Independence, Missouri, Henning’s childhood camping excursions in the Ozark mountains cultivated a lifelong fascination with hillbilly culture. While visiting historical sites on a 15,000-mile road trip across America, Henning was struck with the seed of an idea of how a young Abraham Lincoln would have reacted to the high-speed life along America’s highways. After reading about rural resistance to new highway encroachment in the Ozarks, and surmising it was due to a perceived threat to the moonshine industry, his idea evolved into an out-of-touch Ozark family taking the highway out of the mountains and into the apex of urban modernity. The Beverly Hillbillies, one of the most popular narrative works of art of its era, was his creation.

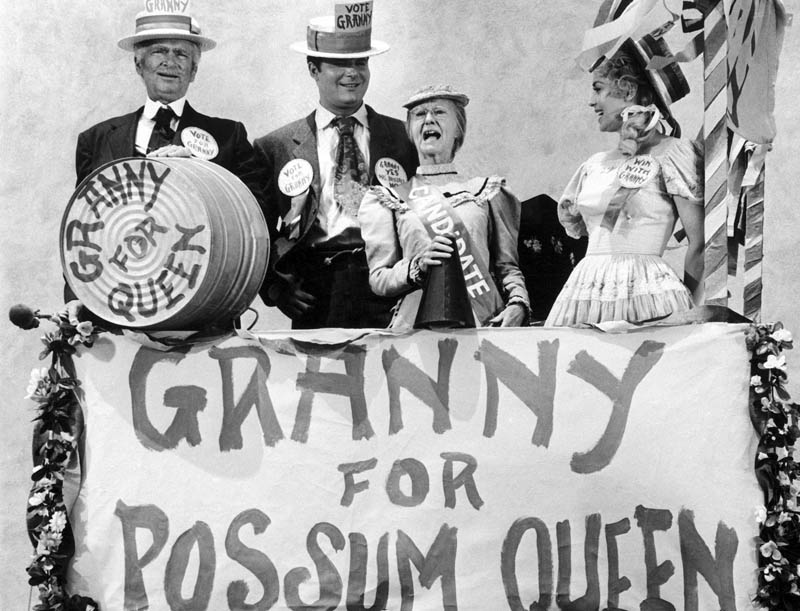

Henning went on to additionally create the renowned rural-based television programs Petticoat Junction and its spinoff, Green Acres, as well as write for The Andy Griffith Show and The Real McCoys. Despite earning fiercely critical reviews, the American public made The Beverly Hillbillies the most-watched show in television history during its first two seasons. From a cultural perspective, the Hillbillies phenomenon had an ironic turnabout: Disproportionately rural, small town, and Southern residents comprised the the immensely popular show’s viewership, despite the widely-understood premise that the show was poking fun at their culture. The highway pipeline between rural and urban values had taken rural culture, processed it through a filter of urban values, and fed it back to rural Americans, who consumed it heartily.

Henning went on to additionally create the renowned rural-based television programs Petticoat Junction and its spinoff, Green Acres, as well as write for The Andy Griffith Show and The Real McCoys. Despite earning fiercely critical reviews, the American public made The Beverly Hillbillies the most-watched show in television history during its first two seasons. From a cultural perspective, the Hillbillies phenomenon had an ironic turnabout: Disproportionately rural, small town, and Southern residents comprised the the immensely popular show’s viewership, despite the widely-understood premise that the show was poking fun at their culture. The highway pipeline between rural and urban values had taken rural culture, processed it through a filter of urban values, and fed it back to rural Americans, who consumed it heartily.

The New Santa Fe Trail

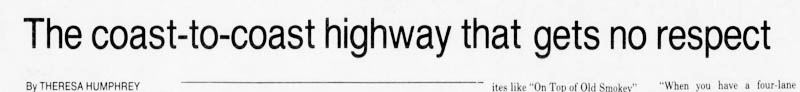

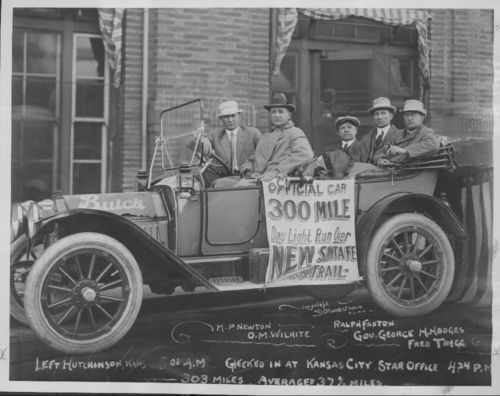

Few states started with poorer roads than Kansas, with its colloquially-known two seasons of sand and mud. Kansans, dependent on the farm-to-market economic pipeline, overwhelmingly supported the national highway concept. The first wave of Kansan’s public enthusiasm centered around the construction of the “New Santa Fe Trail,” a highway roughly following the path of the historical Santa Fe Trail along the Arkansas River, and ultimately Highway 50’s route across the state.

On May 26, 1913, Kansas Governor George Hodges and a carload of Good Roads boosters took a much-celebrated road trip along the New Santa Fe Trail. The 303-mile drive across half the state was completed in just under 9½ hours, and demonstrated the values of speed and independence the new highway system offered to rural inhabitants who had spent generations navigating mud ruts. The road trip also began Kansans’ affinity for the route that became the state’s first paved border-to-border highway in the form of U.S. Highway 50 a decade later. The dedication of Kansas road boosters in stirring rural Kansans to adopt the highway ethic resulted in their local development of 2,500 miles of improved highways between 1909 and 1914, connecting thousands of farmers to urban markets and to the then-understood as inevitable network of national highways.

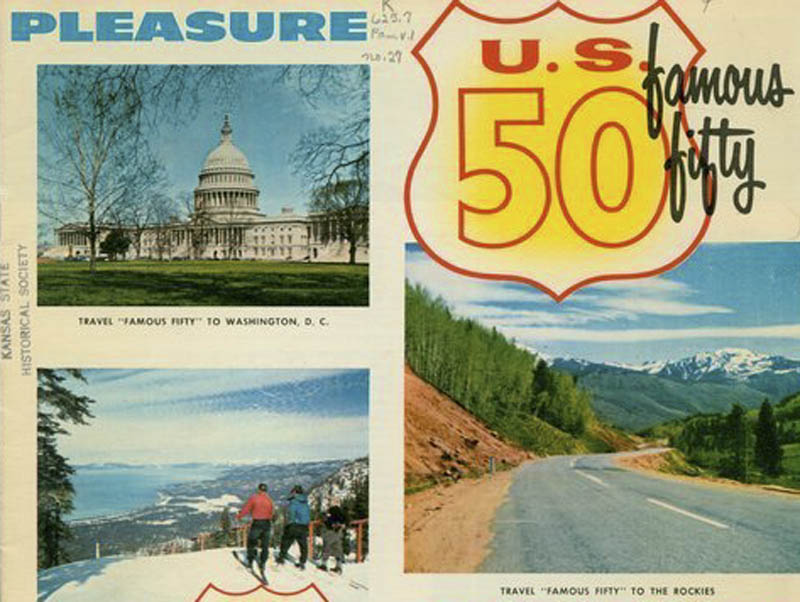

While Kansas led most other states in its highway enthusiasm, each state along Highway 50 maintained its own Highway 50 Association, private organizations serving to promote the highway, its expansion, and act in an advisory capacity to each state’s government with respect to routing decisions. The state associations unified as a national Highway 50 Federation in 1954. As the Good Roads movement had done a few decades prior, the Highway 50 Federation seized existing grassroots sentiments of emerging popular car culture, and promoted travel along Highway 50 using now-entrenched ideas of highways as value-generating networks of freedom and nationalism.

The Highway 50 Federation depicted U.S. 50 as the backbone of America, a “Central Pleasure Route” across the heart of the United States leading straight to the nation’s capital. In the late 1950’s to early 1960’s, the Federation went so far as to hold a series of popular beauty pageants across the 12-state corridor where young women competed for the title of “Miss U.S. Highway 50.” The Highway 50 pageants followed a globally emerging trend in the 1950’s and 60’s of small organizations generating publicity with niche beauty pageants, inspired by the decade’s creation of the Miss World, Miss Universe, and Miss International pageants which continue to this day.

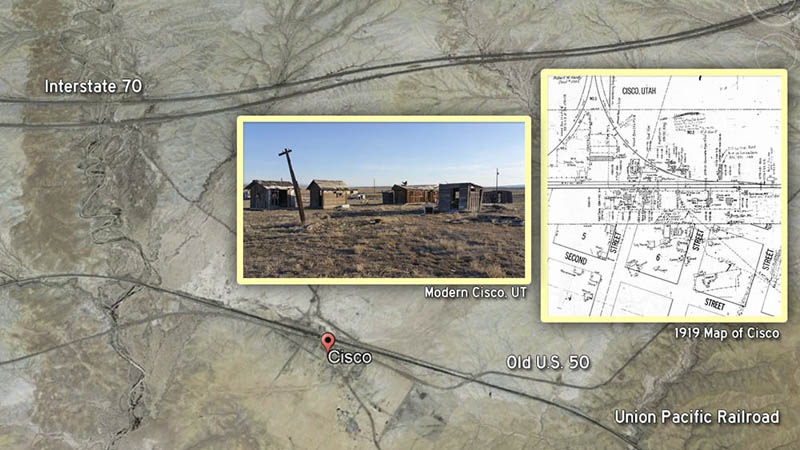

Cisco Clifton’s Fillin Station and Utah’s Uranium Boom

Widespread enthusiasm for America’s “Central Pleasure Route” did not endure, as controversy over Highway 50’s potential place in the 1956 Interstate Highway System, which offered some communities a Faustian pact of reduced congestion at the expense of local businesses. Countless other communities had no choice on the issue. Highway 50’s 100-mile course from Grand Junction, Colorado to Green River, Utah is one of its few sections the Interstate Highway System has completely replaced. Interstate 70’s construction in Utah included an additional 100-mile stretch beyond Green River to Salina through the roadless San Rafael Swell, upon which planners re-routed Highway 50, taking advantage of the more direct route compared to its original course which detoured 150 miles north to Salt Lake City before resuming its east-west orientation in Ely, Nevada.

Little remains of Cisco, the first town Highway 50 meets as this Interstated course enters Utah. The modern ghost town began as a railroad water stop decades before the arrival of the highway. In 1952, Charlie Steen, a geologist residing in one of the town’s far-flung tarpaper shacks, discovered one of the largest uranium deposits in the country at the historical moment of the peak of Cold War nuclear proliferation. Steen’s discovery made him a quick millionaire and turned nearby Moab into a mining boomtown.

The uranium boom in Utah was short-lived, and Cisco was already struggling when Interstate 70 began construction through the area in 1963. Country singer Johnny Cash commemorated the historical moment Interstate 70’s construction passed the town of Cisco into mythology in his 1968 song, Cisco Clifton’s Fillin Station. The story of a Cisco fueling station and its owner’s lament “…I hope my kids stay fed when they build that Interstate,” is likely based on a true story according to a brief oral history of a former Cisco gas station owner taken by Jason Fried, CEO of Basecamp. Fried’s subject claims the song was based on an actual encounter in the late 1960’s and Cash himself was the big-spending Cadillac driver also featured in the lyrics. Today, as predicted in Cash’s song, Cisco sits in near-ruin, completely bypassed by the Interstate. Its major enduring legacy has been as an road-movie ghost town, featured in 1971’s Vanishing Point and 1991’s Thelma and Louise.

Although the state’s construction of the Interstate bypass relegated Cisco to the status of a modern ghost town, recent efforts to breathe life back into Cisco have been led by both long-standing inhabitants and scant newcomers, who have taken to renovating a few of Cisco’s historic buildings. The short section of old U.S. 50 that detours off of Interstate 70 is a brief historic sidetrack from the fury of Interstate travel and offers a quick alternative glimpse at life along the old highway. Cisco’s once-abandoned general store has been restored and rechristened the Buzzard’s Belly General Store, and offers a fantastic historical respite and resupply stop in the midst of an otherwise conventional Interstate highway experience.

“One Must Imagine Sisyphus High on Benzedrine…”

** Movie spoilers ahead **

1971’s Vanishing Point, starring Barry Newman and filmed mostly on or near Highway 50, is a nearly-forgotten masterpiece critiquing the counterculture values of the late-hippy era. The film is the story of a Benzedrine-fueled police chase down the loneliest road in America, from Colorado to California, for no reason than the desperate rush of an adrenaline junkie responding to society’s mishandling of his past honor with seditious rebellion.

The protagonist, a mononymed Kowalski, emblemized the cultural nihilism of that moment in American history – he is an ex-Vietnam veteran and Medal of Honor recipient, an ex-stock car driver, and an ex-cop, dishonorably discharged for challenging his corrupt superiors. Kowalski was ex-everything that idealized masculinity projected in his era, and now stripped of those ranks, he lashes out onto the world in drug-fueled rebellion with no clear motive other than pure impulse; the implied metaphor for American culture at the time is clear.

While critics have consistently dismissed Vanishing Point as a shallow, testosterone-laden money-grab, its deeper existential metaphor and social critiques were lost on most reviewers. The film’s motifs of rebellion, liberation, and institutional corruption are well-seated in its screenwriter’s biography: Vanishing Point’s screenplay was written by none other than Cervantes Prize laureate, and author of Three Sad Tigers, Guillermo Cabrera Infante. Cabrera began his career as a Cuban revolutionary, rising the ranks under Fidel Castro, but was eventually censored in communist Cuba, resulting in his self-exile to fascist-ruled Spain. Enduring additional censorship under Franco, he ultimately landed in London just four years before Vanishing Point’s 1971 release. Having lived under two brands of totalitarianism, Cabrera’s script is a critique of the authoritarian underpinnings that were growing from the cultural nihilism of both American countercultural movements and the western intelligentsia alike.

Vanishing Point’s standout feature is its philosophical and mythological framework. Cabrera hybridized the Greek myth of Sisyphus and Homer’s Odyssey in crafting the character of Kowalski, and used the setting to critique American society and specifically the growing schism within the existentialist philosophies that were leading the counterculture of the era.

The elements of Homer’s Odyssey are readily apparent in the plot, as Kowalski repeatedly rejects tempting siren calls of lecherous women threatening to obstruct his journey. Vanishing Point was also a breakout role for actor Cleavon Little as blind radio host Super Soul, who aids Kowalski by broadcasting the pursuing police’s strategies across the Great Basin. As Kowalski’s ethereal guide, Super Soul is a blind man with the gift of music and lore, standing in for the Odyssey’s Demodocus. Three years later, Super Soul actor Little would leave an indelible mark in Hollywood infamy as the lead role in Mel Brooks’ Blazing Saddles.

For the crimes of enchaining death such that humanity would never suffer its sting, and for exposing a corrupt affair between the gods, Greek mythology’s Sisyphus was condemned to push a boulder to the top of a hill, only to watch it roll back to the bottom each time, for eternity. Similarly Kowalski defied death as a soldier and professional racer, learned contempt for it witnessing his lover drown, and stood up to his corrupt police superiors to prevent a sexual assault. Kowalski’s past resulted in his dishonorable discharge from the police force and subsequent life of delivering cars from Colorado to San Francisco and back along the loneliest road in America.

The philosopher Albert Camus used the myth of Sisyphus to convey his absurdist philosophy as an antidote to the nihilism of the modern era. Rather than despairing through his meaningless condemnation, Camus suggested “One must imagine Sisyphus happy.” Kowalski’s assured smile as he speeds towards oblivion reflects precisely this philosophy, rendering him an “absurd hero” of his generation.

The many people Kowalski encounters on his odyssey are all social dropouts- hippies, bikers, street racers, and religious zealots. They are aligned with him as members of the counterculture, but Kowalski’s distinction, which keeps him returning to the highway, is that he is just fine with the corrupt system the way it is; rather than dropping out, Kowalski delights in his role as an active rebel, not hiding from the police but antagonizing them as often as possible. All of these characters are rooted in nihilism, but their relationship to each other is an allegory for the 1960’s philosophical schism between the post-structuralist existentialists who followed the emerging tradition of Jean-Paul Sartre, and the adepts of Albert Camus’ absurdism. Sartre advocated the Marxist tradition of permanent revolution regardless of human cost, whereas Camus argued for rebellion over revolution, maintaining that Utopian ends did not justify means such as terroristic violence against civilians. This intellectual distinction would not have been wasted on Cabrera, who lived under two brands of totalitarianism in communist Cuba and fascist Spain and now found himself in the liberal Western world.

Whereas Kowalski encounters the rest of the counterculture rejecting the system to live on the periphery of society in a state of permanent and futile revolution against mainstream hegemonic values, Kowalski himself embraces the system head-on, fueling his rebellion with the futility of his own existence. He is not frightened by the systemic injustice or nihilism that has continuously dethroned him, he is excited by it. His life, and total acceptance of his inevitable death, is an act of rebellion that Camus would be proud of.

Kowalski blows through stop signs without regard for the power structures they represent. Super Soul defiantly dances in front of a large stop sign outside his studio’s window, unaware it’s even there. Meanwhile the Utah State Troopers pursuing Kowalski abruptly pull over just as they are finally overtaking him, revealed moments later due to the “Welcome to Nevada” sign that signals their jurisdictional limits. Signage, and the arbitrary authority it represents, is a character of its own in the film.

Moments before the film’s finale, the camera lingers on yet another stop sign Kowalski speeds through. The next scene is Super Soul’s single word finale, a pleading “STOP!” yelled towards the sky, suggesting the limits of the power of rebellion. Literal suicide is the ultimate act of rebellion against reality, but it is one Camus argued strongly against. In becoming the ultimate rebel, Kowalski misses the vital lesson that any path of pure rebellion will inevitably lead to suicide if not tempered.

A subtle visual cue in the film’s opening, as Kowalski charges towards the bulldozer-barricade, is a black car passing Kowalski in his final moment, headed in the opposite direction. Given the barricade, the black Ford LTD could not logically be coming from anywhere. The camera freezes on the moment of the two car’s passing, zooms in, Kowalski’s car fades from existence, and the camera then follows the black Ford in the opposite direction before the rest of the film begins as a flashback in Colorado. This scene lasts only a few seconds but is pivotal to establishing the premise that death brings Kowalski back to Colorado to begin his cycle anew.

Vanishing Point highlighted Highway 50’s route through central Utah and Nevada, and was filmed as construction began on the section of Interstate 70 that would ultimately bypass much of 50’s parallel route. In a sense, the film is a time capsule to the last moments for hundreds of miles of the highway, perhaps a final sentiment of righteous rebellion against the hegemony of the coming Interstate culture. The opening scene and finale were filmed in Cisco, Utah, re-imagined as a California border town.

While Vanishing Point had deep cultural and philosophical influences, the movie itself went on to substantially influence American culture as well. Movie car chases have existed since film’s emergence as a medium, but of Vanishing Point’s many contributions is being the first film for which the car chase was the entire premise, unleashing a genre that extends to today’s Fast and Furious and Mad Max film franchises.

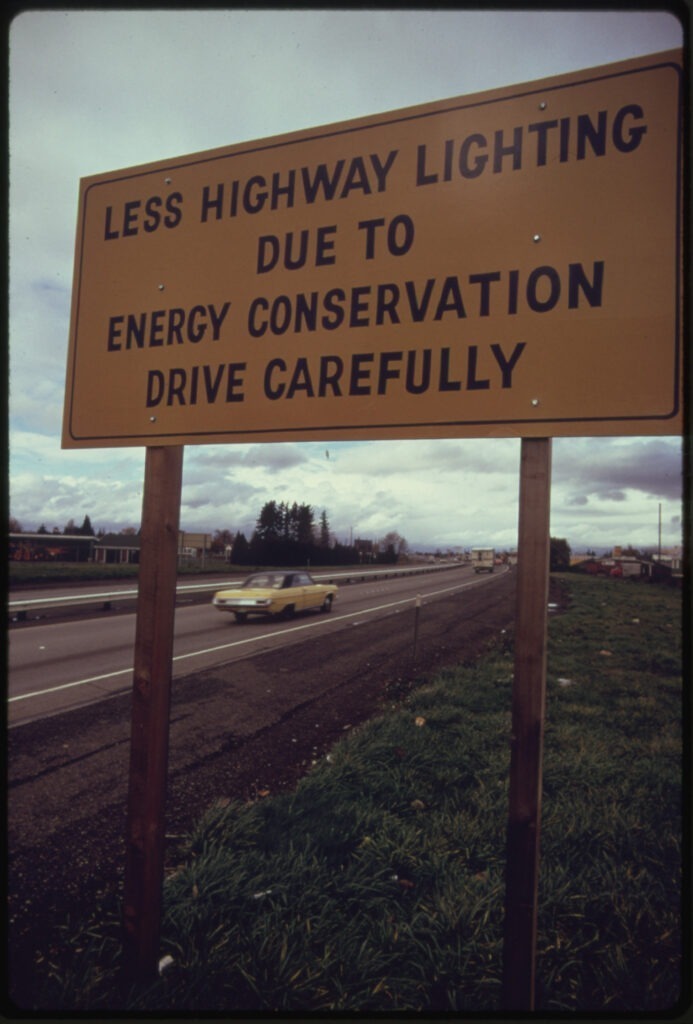

Kowalski’s car, a 1970 Dodge Challenger R/T 440 Magnum, brought as much of a presence to the screen as the star of the film. Vanishing Point surged public demand for pony cars – affordable high-performance smaller models such as the Ford Mustang, Pontiac Firebird, and Chevy Camaro, bringing the performance craze instigated by true muscle cars within reach of the working class. America’s growing cultural dependency on these performance vehicles proved to be a point of geopolitical vulnerability two years later when the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) enforced an oil embargo on countries that supported Israel during the Yom Kippur War of the same year.

The embargo skyrocketed the price of gasoline while producing shortages and demanding fuel rationing nationwide. The results in the United States were long lines at gas stations, electricity rationing, and the 1974 Emergency Highway Energy Conservation Act which enacted a National Maximum Speed Limit, forbidding states from allowing highway speed limits over 55 miles per hour in order to reduce fuel consumption. The controversial regulation endured until 1995.

The 1973 Oil Crisis momentarily chilled the pony car craze and eventually shocked the majority of Americans into valuing fuel economy over performance. Despite a brief resurgence in pony car demand towards the end of the 1970’s (led by Vanishing Point’s cinematic descendant Smokey and the Bandit and television’s Rockford Files and The Dukes of Hazzard) the tide ebbed with the turn of the 1980’s and the era of economy vehicles became a dominant feature in American culture thereafter.

Although Vanishing Point has passed into further obscurity with subsequent generations, and its “product of its era” classically liberal attitude is dated by modern standards, the exaggerated cry of the name Kowalski has long lingered as an inside joke among auto mechanics and racing enthusiasts to this day.

Vanishing Point’s star, Barry Newman, passed away in early 2023 at the age of 92.

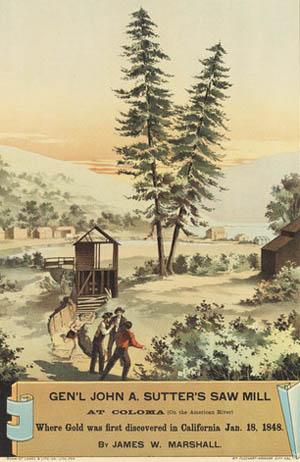

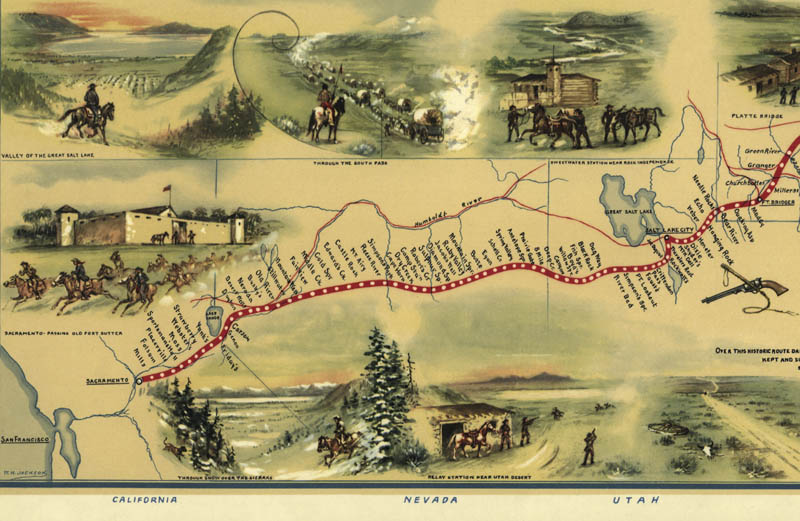

California’s Gold Rush

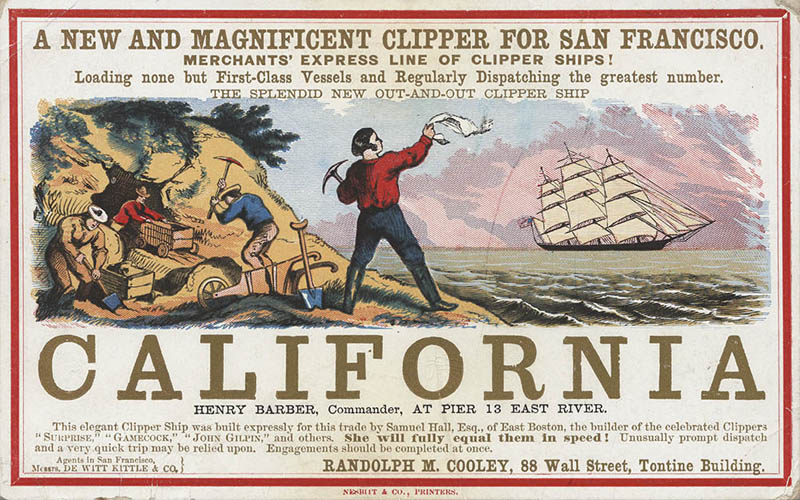

The nearby nexus point of California’s modern history lays just north of Highway 50’s passage across the Sierra Nevada Mountain Range. A sawyer named James Marshall discovered gold at the mining settlement of Coloma in 1848 while building a mill for prominent landowner John Sutter. Marshal’s discovery sparked the California Gold Rush, one of the largest mass-migrations in American history, permanently establishing the state’s economic and political primacy in the United States.

Just after Marshal’s discovery, John Sutter’s son established the City of Sacramento in order to capitalize on the incoming mining rush. Sacramento’s quick success as California’s first incorporated city made it a destination for thousands of new immigrants to the region. Seven months after the incorporation of the City of Sacramento, California contentiously entered the Union as a free state on September 9, 1850. Four years later, Sacramento became the new state’s capital. Hundreds of thousands of migrants from all over the world converged on California’s remote gold fields in the ensuing decades, creating dozens of trails and laying the foundation for the future highway system.

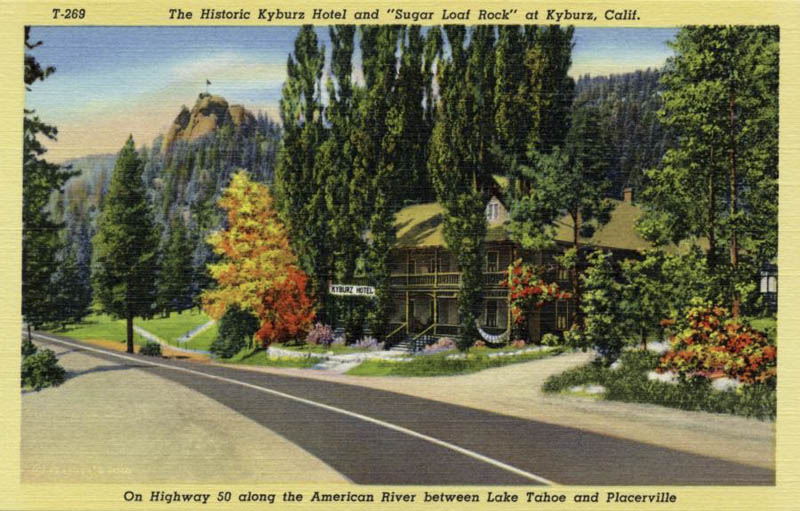

The California Trail, the era’s most popular overland migration route into the state, brought thousands to the mining frontier. One of the trail’s most popular branches, Johnson’s Cutoff, ultimately became Highway 50’s path into California. The cutoff was named for John Calhoun Johnson, a Placerville lawyer who cleared a toll road from the Lake Tahoe basin to the South Fork of the American River, creating the most direct route between Carson City, capital of Nevada, and Sacramento. Johnson’s 1852 project was the first intentionally-created road across the Sierra Nevada mountain range which otherwise divided most of California from the rest of the United States. In 1853, the town of Placerville assembled an ad hoc committee to clear the river route to Johnson’s cutoff, collecting $1,600 for the effort with hopes of the route becoming a major path for gold-seekers and bolstering Placerville’s economy; Sierra Nevada towns now competed to improve their mountain roads for the sake of their respective economies, each pioneering the age of publicly-funded roads well ahead of the National Highway System. In 1862, the Central Pacific Railroad stationed an agent to count all traffic passing through the Tahoe Wagon Road to Johnson’s cutoff; he estimated toll-takers along the way earned 1.1 million (unadjusted!) dollars per year off the venture.

It was Johnson’s route the fabled Pony Express followed through the Sierra Nevada to Sacramento during its brief, 18-month life as a mail relay, allowing the relatively speedy 10-day transmission of information to and from the East Coast. In a pattern echoed in the future with highways and rural electrification, the first transcontinental telegraph closely paralleled the Pony Express Trail, and put the Express out of business the day after its first transmission. The State of California acknowledged the importance of this route when it adopted the Lake Tahoe Wagon Road as its first state highway in 1896. California created its second state highway days later, connecting Sacramento to the town of Folsom. Highway 50 annexed both roads a few decades afterwards.

Thus far, we’ve approached human migration from a perspective of net-benefit. The migrations inspiring the creation of Highway 50 in California, however, had catastrophic results for its existing rural residents. As Gold Rush mining roads branched from these migration arteries, settlers drew ever-deeper into Native territories; confrontation was inevitable. In Governor Peter Burnett’s State of the State address of 1851, he accurately forecast the next few decades: “That a war of extermination will continue to be waged between the races until the Indian race becomes extinct must be expected. While we cannot anticipate this result but with painful regret, the inevitable destiny of the race is beyond the power or wisdom of man to avert.” The nearly-successful extermination of entire bands of California Natives in the first three decades of the Gold Rush, achieving an approximate 80 percent depopulation rate, is today approached by many historians as an ethnic cleansing.

Interstated

The success of the U.S. Numbered Highway System seeded its own downfall; by mid-century, the highways simply became too popular for their own good. America’s wholesale embrace of car culture created widespread social and environmental ills as traffic clogged small towns and large cities alike. Highway planners originally routed numbered highways along existing roads into the centers of towns and cities, logical destinations in the era before mass congestion. Traffic, noise and accidents motivated later road planners’ decisions to route new highways around towns rather than through them. Interstates required new construction, and typically followed engineered surveys, rarely taking into account local settlement patterns. In the 1950’s and 60’s, broad sectors of industry and government widely supported the Interstate system that subsequently dominated America’s cultural landscape.

America’s most popular highway, Route 66, was unceremoniously plowed over and largely replaced by Interstates 40, 44, and 55. While Highway 50 largely escaped this fate, its entire corridor now faces direct competition with the more efficient, safer, and consistent Interstate Highway System, a similar economic destiny to C.R. Patterson & Sons and the independent women entrepreneurs of Ocean City. Perhaps an ironic turnabout in economic history, the limited-access Interstate expressway system mimics early named auto trail routes, which envisioned a highway as an isolated line between two cities with a series of subscribed destinations along its path. This pattern is also analogous to the economics of river, canal, and rail transportation, where rural development was determined according to proximity to transportation network outlets. Similar to top-down suburban planning, the Interstate system did not allow for spontaneous roadside developments. Corporate franchises, able to afford the now commodified land surrounding freeway exit ramps, succeeded autocamps, roadhouses, and farm stands that once emerged at crossroads and river bends along old numbered highways.

Eminent domain, the mechanism by which many Interstate routes obtained their land from private owners, affected Nevada ranchers and St. Louis ethnic neighborhoods alike. As the national economy and culture followed the Interstate, those parts of the country not covered by the system found themselves under-served by the accelerating trend of interconnectivity. The limited-access nature of the Interstate system gave it an increasingly urban focus. From an economic standpoint, the Interstates follow a colonial model compared to the more free and spontaneous numbered highways, favoring homogeneous off-ramp corporate franchise economies over independent local businesses.

Today, the United States Numbered Highways and the Interstate Highway System exist together as complimentary networks. The Interstate system has assumed economic and cultural primacy over the course of the last few decades, at the expense of small-town economies. The process has unevenly polarized the evolution of the urban-rural cultural divide, presenting as hyper-homogenization of culture for the majority of people who live along Interstate corridors, while regressing the divide’s narrowing trend for the geographic majority of America not served by the Interstate system.

Highway 50 in Obscurity

The Interstate system overwhelmingly avoided Highway 50’s corridor, rendering it a living museum to the cultural network left behind by the Interstate revolution. Culture, within the automobility framework, follows a similar pattern to the fueling network. Highways are a pipeline for cultural transmission from country to city, where culture is refined, homogenized, and redistributed back to countryside. Music, televised narratives, human settlement patterns, and trade networks each principally followed the highway pipeline to connect disparate urban and rural cultures, and are strongly influenced by the values of automobility along the way. As folk and blues musical genres exported from country to cities in the form of hillbilly and race, they evolved into separate tracts of country and R&B, only to later reunite in rock and roll as automobility values became mainstream.

Rural narratives followed a similar path in the hands of urban television writers. The highways influenced technological culture as the internal combustion engine evolved from an element of rural

utility to one of urban luxury, establishing itself as the dominant technological feature in American society. Trade networks evolved out of Appalachian Development Corridors and rum running bootlegging routes into franchise uniformity to the peril of the independent entrepreneurs of Ocean City and rural auto manufacturers in Southern Ohio alike. Urban planners’ efforts to create pastoral utopias through suburban development omitted the value of sustainability that enabled rural residents to endure generations of hardship. The distant Interstate system amplified all these effects, resurrecting a model more akin to the river, canal, and rail systems the highways were meant to replace.

The highway system, as a network, generates the value of freedom above all others. While this value of the highway has been popularly explored in the subjective world of literary and musical

narratives, its most useful manifestation is the highway’s ability to enable individuals the choice of where to live and where to work, despite geographic obstacles, by significantly reducing the economic challenges to intra-national migration. The traditional consideration of automobile ownership as an economic barrier to the highways crumbled quickly as bus services extended routes into the countryside and hitchhiking came into vogue.

Individual named and numbered Highways are ultimately arbitrary concepts. The idea of an individual highway is a metaphysical notion, held only in the minds of the idea’s adherents. This is a status shared by political borders; from a historical perspective, Highway 50 can be conceived of as a nation in itself. As virtually all streets in America are interconnected, every road could also be seen more practically as a single highway. American highways are consistently re-routed, decommissioned, and in many cases bulldozed-over by the Interstate system. Yet since the era of early traces and trails, Americans have expressed a habit of naming and sentimentalizing their routes, regardless of their pragmatic or bureaucratic origins. As the nation’s enduring nostalgia for Route 66, formally decommissioned in 1985, demonstrates, belief in a Highway is ultimately an act of faith, one in which most Americans choose to engage.