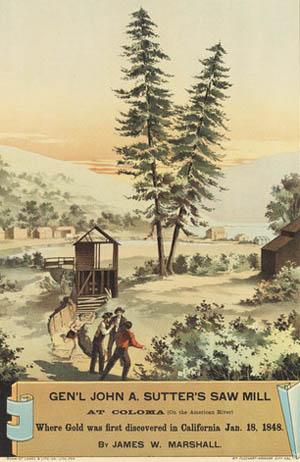

The nearby nexus point of California’s modern history lays just north of Highway 50’s passage across the Sierra Nevada Mountain Range. A sawyer named James Marshall discovered gold at the mining settlement of Coloma in 1848 while building a mill for prominent landowner John Sutter. Marshal’s discovery sparked the California Gold Rush, one of the largest mass-migrations in American history, permanently establishing the state’s economic and political primacy in the United States.

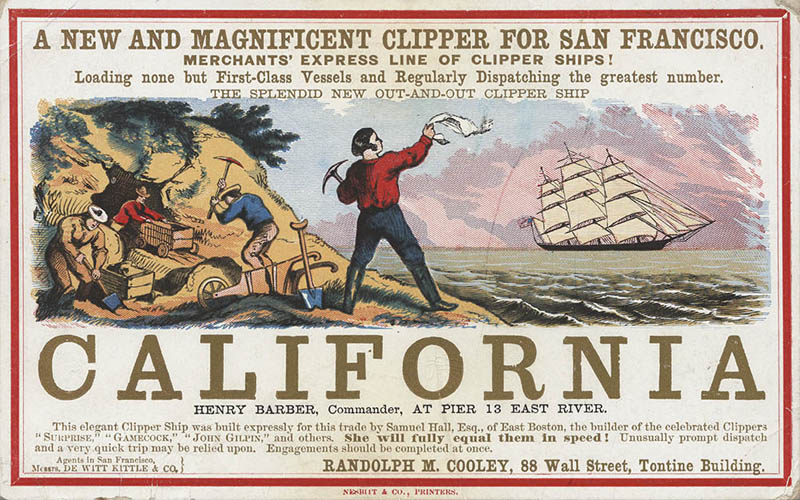

Just after Marshal’s discovery, John Sutter’s son established the City of Sacramento in order to capitalize on the incoming mining rush. Sacramento’s quick success as California’s first incorporated city made it a destination for thousands of new immigrants to the region. Seven months after the incorporation of the City of Sacramento, California contentiously entered the Union as a free state on September 9, 1850. Four years later, Sacramento became the new state’s capital. Hundreds of thousands of migrants from all over the world converged on California’s remote gold fields in the ensuing decades, creating dozens of trails and laying the foundation for the future highway system.

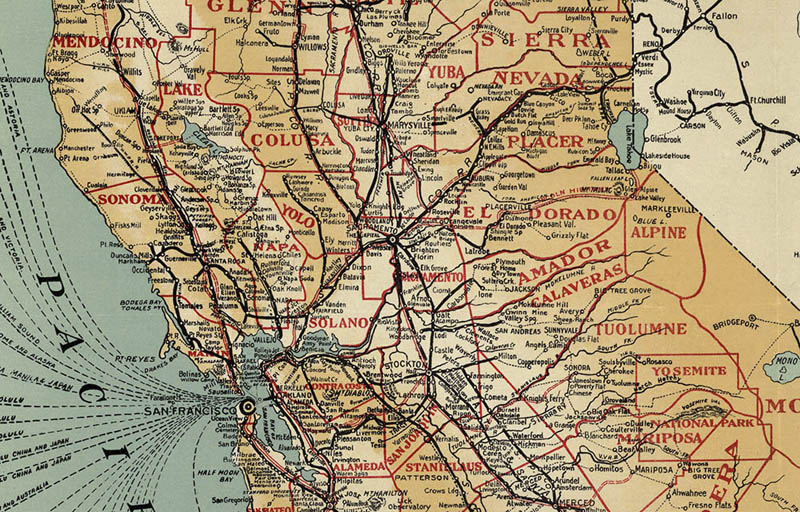

The California Trail, the era’s most popular overland migration route into the state, brought thousands to the mining frontier. One of the trail’s most popular branches, Johnson’s Cutoff, ultimately became Highway 50’s path into California. The cutoff was named for John Calhoun Johnson, a Placerville lawyer who cleared a toll road from the Lake Tahoe basin to the South Fork of the American River, creating the most direct route between Carson City, capital of Nevada, and Sacramento. Johnson’s 1852 project was the first intentionally-created road across the Sierra Nevada mountain range which otherwise divided most of California from the rest of the United States. In 1853, the town of Placerville assembled an ad hoc committee to clear the river route to Johnson’s cutoff, collecting $1,600 for the effort with hopes of the route becoming a major path for gold-seekers and bolstering Placerville’s economy; Sierra Nevada towns now competed to improve their mountain roads for the sake of their respective economies, each pioneering the age of publicly-funded roads well ahead of the National Highway System. In 1862, the Central Pacific Railroad stationed an agent to count all traffic passing through the Tahoe Wagon Road to Johnson’s cutoff; he estimated toll-takers along the way earned 1.1 million (unadjusted!) dollars per year off the venture.

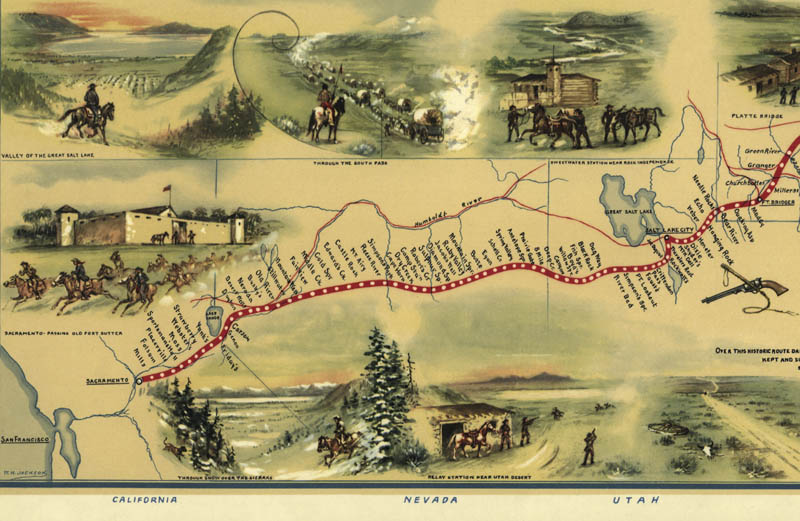

It was Johnson’s route the fabled Pony Express followed through the Sierra Nevada to Sacramento during its brief, 18-month life as a mail relay, allowing the relatively speedy 10-day transmission of information to and from the East Coast. In a pattern echoed in the future with highways and rural electrification, the first transcontinental telegraph closely paralleled the Pony Express Trail, and put the Express out of business the day after its first transmission. The State of California acknowledged the importance of this route when it adopted the Lake Tahoe Wagon Road as its first state highway in 1896. California created its second state highway days later, connecting Sacramento to the town of Folsom. Highway 50 annexed both roads a few decades afterwards.

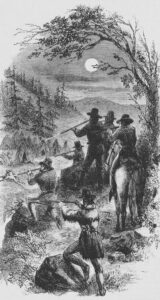

Thus far, we’ve approached human migration from a perspective of net-benefit. The migrations inspiring the creation of Highway 50 in California, however, had catastrophic results for its existing rural residents. As Gold Rush mining roads branched from these migration arteries, settlers drew ever-deeper into Native territories; confrontation was inevitable. In Governor Peter Burnett’s State of the State address of 1851, he accurately forecast the next few decades: “That a war of extermination will continue to be waged between the races until the Indian race becomes extinct must be expected. While we cannot anticipate this result but with painful regret, the inevitable destiny of the race is beyond the power or wisdom of man to avert.” The nearly-successful extermination of entire bands of California Natives in the first three decades of the Gold Rush, achieving an approximate 80 percent depopulation rate, is today approached by many historians as an ethnic cleansing.