“It’s totally empty. There are no points of interest. We don’t recommend it… We warn all motorists not to drive there, unless they’re confident of their survival skills.”

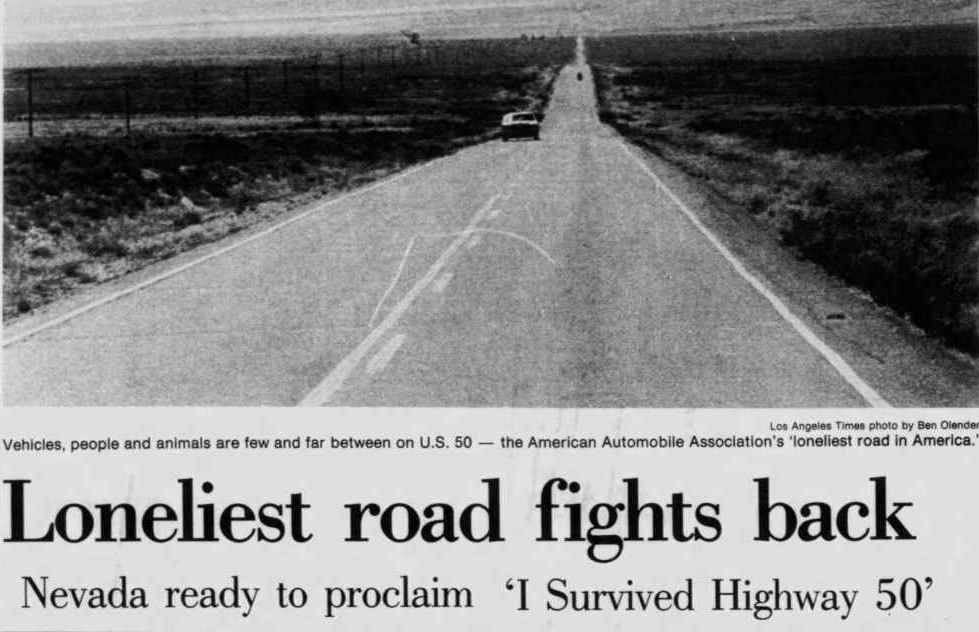

This American Automobile Association description, under the heading “The Loneliest Road,” appeared in a 1986 issue of Life magazine, referencing U.S. Highway 50’s course through the State of Nevada. Many residents along the highway’s 3,073-mile route took consternation from the phrase, recalling the transcontinental highway had once been a contender for the “Main Street of America.” The State of Nevada, on the other hand, saw the highway’s new-found infamy as an opportunity; less than a year later, the state legislature took ownership of the “Loneliest Road” moniker and began signing the highway as such. The Life magazine blurb erupted a war of letters in newspapers from Tallahassee to Boston to San Bernardino, each weighing in on the nearly-forgotten highway. The road’s newfound status as an issue of national concern was substantial enough to bring with it a public debate on the creation of nearby Great Basin National Park, approved by Congress just three months later.

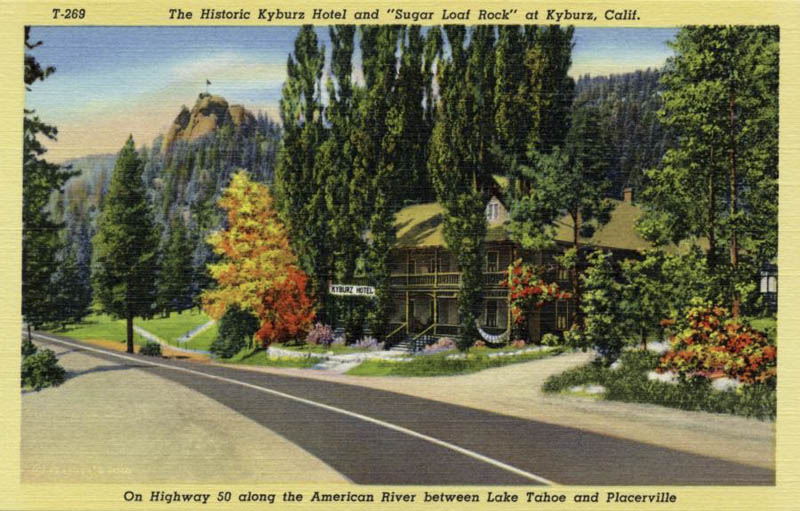

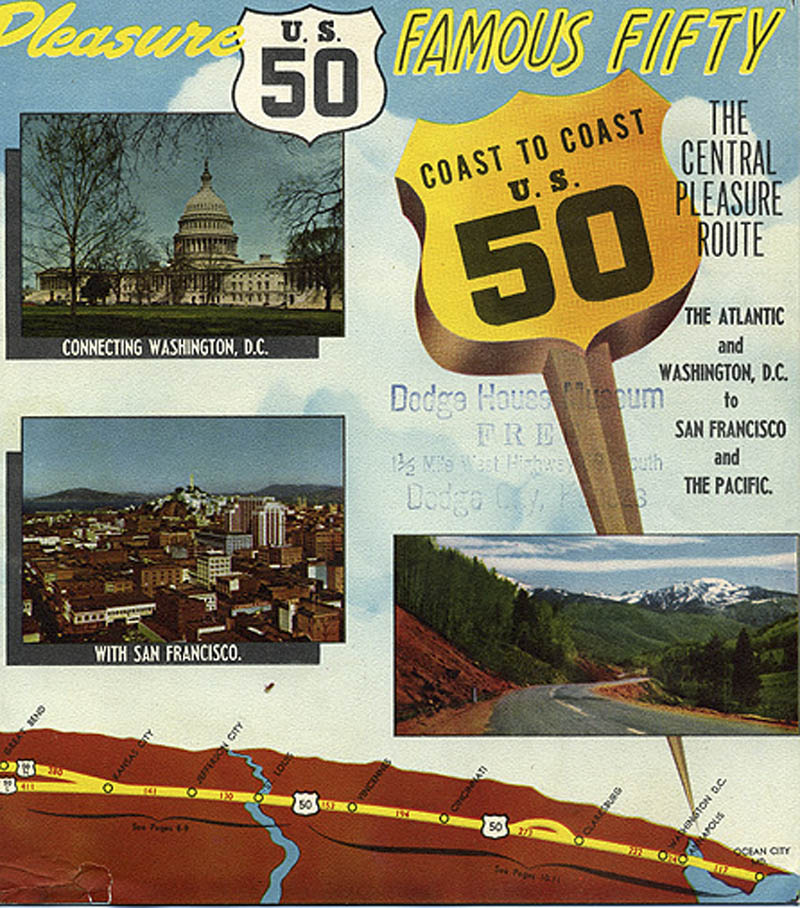

The course of Highway 50 coincides very closely with the geographic center of the conterminous United States. The highway encounters a significant diversity of subcultures along its path, making it a useful vector for analyzing American cultural history. Highway 50 winds from the cities of Washington, D.C., Cincinnati, St. Louis, Kansas City, and Sacramento, to the remote mountains of the West Virginia Appalachians and Colorado’s Rockies, to the vast farming country of the Midwest and Ohio River Valley, and ultimately through the now-legendary loneliness of Nevada and Utah’s Great Basin Desert.

The formal designation of Highway 50 with the passage of the 1926 United States Numbered Highway act is a convenient point of historical origin for the route, but the exact date of the route’s creation is a more complicated question. Some of the highway’s various passages follow old traces tracking back to prehistoric game trails, while others are presently rerouting as new construction in places where no path has ever laid. Here, we view the road in all its manifestations, regarding it from the several historic routes formally named Highway 50, as well as the old traces, trails, railbeds and even game trails the highway was routed along.

To understand the impact Highway 50 had on culture along its route, first consider what the United States looked like at the turn of the 20th century before the Numbered Highway System existed: Other than walking, horses were the primary mode of transportation in both city and country. The transcontinental rail routes completed a few decades earlier allowed for transporting people and goods throughout the frontier west, but their fixed routes presented significant geographic limitations. Long-distance transportation was still a rare, generally once-in-a-lifetime event, and usually undertaken via navigable waterways.

Passenger vehicles were a very rare site, held by a small, wealthy cadre of urban enthusiasts keeping ahead of the masses who had recently embraced a global bicycle craze. Paved roads were also a rare site, confined almost entirely to cities, and built at the behest of bicyclists. The turn of the century quickly fueled a new craze for automobiles, rapidly supplanting bicycling as the en vogue assertion of individuality and freedom for those who could afford them. By 1915, the recently-formed National Highway Association began a mass media campaign for “Good Roads Everywhere,” with their bronze icons of an eagle carrying the globe in its talons becoming a common site on radiator caps nationwide. The association released vibrant, full-color maps revealing a vision of the United States that could be: a webbing of black and red highways connecting every city, while passing through green national forests, yellow reservations, and purple National Parks. Nationalism and manifest destiny were unambiguous themes throughout this campaign, maintaining lock-step with the national defense themes that dominated American culture during World War I. The superlative themes of these propaganda pieces were not out of line; the Federal Highway System they proposed would become the biggest public works project in human history.

With the dawning of the Interstate expressway revolution of the late 1950’s, which was intent on replacing the then highly-congested Numbered Highway System, enthusiasm for Highway 50 as a contender for “America’s Main Street” began to fade. Debates over the value of the Interstate’s pioneering economy against its habit of bypassing small towns resulted in Highway 50’s corridor being almost entirely bypassed by the new Interstate Highway system. In the wake of this decision, small towns along the 50 endured, but did not thrive. Today Highway 50 remains, decades after the decommissioning of some of its more famous counterparts, a living museum of the culture left behind by the Interstate revolution. Owing to its geographic diversity, the highway also offers a useful cross-section of the evolution of American culture through its many historical intersections.

This digital museum is an exploration of the history along Highway 50’s cultural corridor, not only to understand the multitude of subcultures along the highway’s path, but also as a means of understanding the United States’ history as a whole, by treating the highway as an arbitrary and objective framework to explore the country’s broader historical patterns and relationships.

You can support this project directly through Buy Me A Coffee!