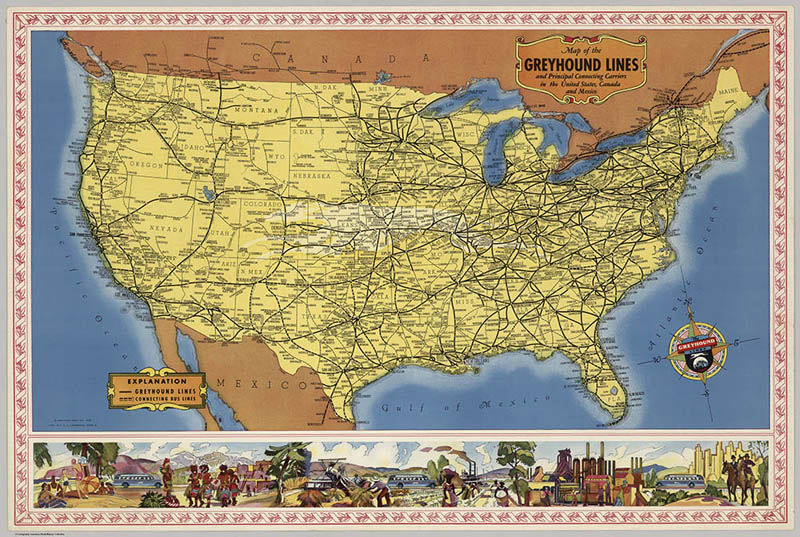

Highway 50 transects regions of extreme rurality and metropolitan centers alike on its path across America. Perceptions of an urban-rural divide between the two dispersive regions has always been an axiomatic aspect of American politics, from Thomas Jefferson’s 1803 description of cities as “the sinks of voluntary misery,” to Barack Obama’s 2008 rural dismissive “they get bitter, they cling to guns or religion or antipathy to people who aren’t like them… as a way to explain their frustrations.” The division has persistently defined national politics and shows no sign of fading from the public mind. Today, more than half of rural and urban residents respectively believe the other side of the divide holds completely different values from them. While America’s urban-rural division remains a popular target for political pundits to exaggerate differences between Americans, the cultural historical perspective shows this divide has rarely been narrower: Tracing the evolution of cultural values like freedom and nationalism on each side of the divide during the twentieth century reveals the United States Highway System as the prime instigating factor in drawing the two cultures closer together. Cultural values across the divide remain distinct today, but comparing that distiction to where it was a century ago demonstrates a dramatic narrowing. As American culture evolved with the highway network, the system effectively narrowed the cultural gap between rural and urban America by connecting the two at a human level. Suburban development, enabled by the highway system, best exemplifies the homogenization represented by this narrowing.

Ahead of the highway era, rural residents paid a material cost for foul road conditions in the form of broken wagon axles and losses in time spent between repair and extrication. Farmers largely regarded these losses a de facto regressive tax on their products. In 1918, the United States Department of Agriculture calculated the operating cost per ton-mile of corn, wheat and cotton transported by motor vehicle as costing half that of traditional wagon transport. The National Highway Association (One of several Good Roads organizations then in operation) highlighted these and other economic and social costs in a national mass-media campaign, printing and distributing an average of 14,000 pamphlets, maps, and bulletins each day of 1916, by its own accounting. The Good Roads movement’s propaganda coup seized on farmers’ ongoing frustration, and by the 1920’s most rural Americans had joined urban elites in enthusiastically supporting the national highway concept.

Other than walking, horses served as the most common means of transportation in the era before automobiles. For urban and rural travelers alike, equine feeding and upkeep proved a formidable expense, as animals needed to be fed daily, year round, whether ridden or not. In 1900, approximately one third of cropland in the United States was dedicated to growing hay for feeding horses. The burgeoning used car market following World War I proved automobiles a more cost-effective alternative to horses even before the creation of the first numbered highways. The 1920’s and 30’s progressed as an explosion of highway improvement and new construction nationwide.

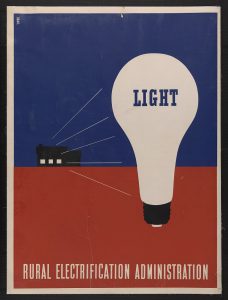

Highways offered farmers expanded access to distant markets, while significantly decreasing expenses. The system also instigated infrastructure improvements following each new highway, offering easy maintenance access to utility lines along the network’s furthest reaches. The highways thus brought electrification to rural America, and along with it came radios, television, and eventually the internet, each beginning as a primarily urban phenomenon. These mediums increasingly exposed rural Americans to urban culture, as cities, holding the bulk of infrastructure and media talent, produced the majority of syndicated radio and television programming. The rapid expansion of access to radio newscasts contributed to a slow supplantation of the provincialism of rural America with a growing sense of nationalism. While broadcast media established a new national narrative, the highway system provided a tangible link to nationalist values such as manifest destiny. National identity was far more tangible for the hundreds of small towns along Highway 50, as the National Highway System connected each town’s Main Street directly to Washington, D.C.

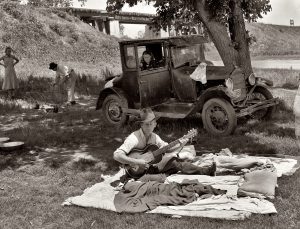

By 1925, as improved roads began to reach deeper into rural America, motor vehicles transported 75 percent of California’s farm produce and 90 percent of Connecticut’s. Highways had the added benefit of allowing rural residents easy access to centralized education and medical care, once the sole province of urban life. Through increasing the mobility of labor, highways also brought farmers the freedom to continue farming in the face of an increasingly fickle labor market, particularly during the World Wars. Automobility also liberated farmers from complete dependence on human labor, as some farmers would remove the rear wheels from cars and trucks and replace them with farm implements to create improvised tractors. On the other hand, the same freedom enabling farmers to stay on their land also lured a younger generation towards the romance of distant cities. Restless youth, exposed to media depictions of cosmopolitan cities now a mere bus ride away, challenged the once-given intergenerational nature of farming. The population of rural America only slightly changed over the course of the twentieth century, very slowly increasing from 46 million people in 1900 to 62 million at the turn of the millennium. Urban and suburban communities represented the vast majority of population growth in the United States during this hundred-year period. While contributing to rural emigration towards cities, highways also brought urban diseases to the countryside; in the days before the development of motels or auto camping infrastructure, early auto campers driving from cities informally camped on the sides of roads. Their contribution of a sudden influx of roadside litter and human waste into local streams introduced minor epidemics of Typhus and other urban diseases otherwise uncommon in the countryside.