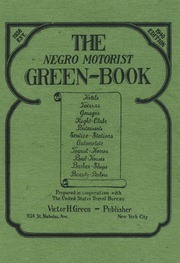

Compared to earlier transportation models of rivers, canals, and railroads, the highway system democratized access to travel and migration. The highway experience for black Americans, however, was marked by challenges not experienced by white travelers. The 1920’s saw an explosion in Ku Klux Klan memberships, and hundreds of rural “sundown towns,” including many along Highway 50, embraced the exclusion of blacks after sunset. Freedom to travel does not imply security in doing so; the vulnerability accompanying the isolation of rural highways inhibited leisure travel for many black Americans in the 20th century. Corrective measures, including Victor Green’s publication of The Negro Motorist’s Green Book, a guide to black-friendly traveler services across the country, took much of the guesswork out of avoiding awkward and often dangerous situations for motorists. The Green Book celebrated the highway as a venue for expanding black liberation in America. An article by trade school president Benjamin Thomas in the 1938 edition highlighted the economic advantages the automotive boom offered blacks to escape the service class into the mechanical middle class. Thomas touted entry-level automotive work, as both a chauffeur’s or mechanic’s starting wages earned three-times the typical service wages of black Americans at the time.

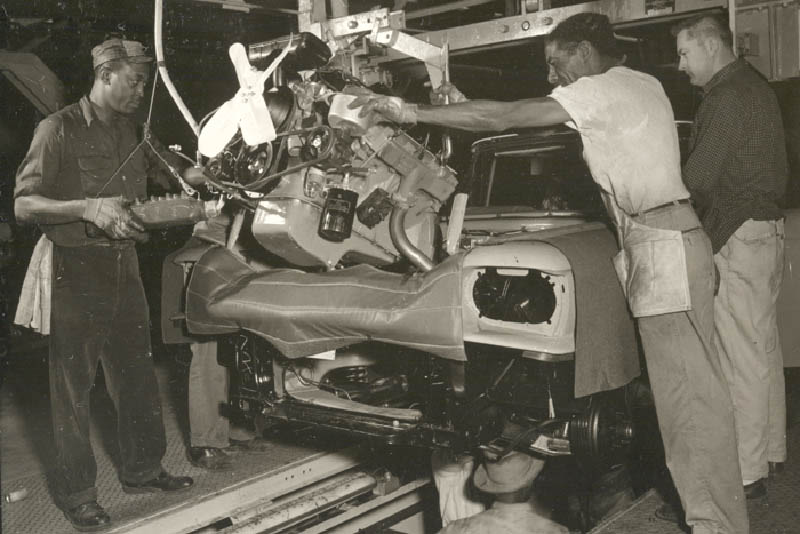

The Great Migration of roughly six million black Americans from the rural South into Northern cities through the mid-twentieth century maximized the highway system’s ability to empower individual self-determination in the face of brutal circumstances. While offering freedom from oppression in the South, the Great Migration also enabled the freedom to pursue economic opportunities provided by the automotive manufacturing cities of the North. Although black employment in the industry was still scant at the time of Thomas’ writing, the era during and after World War II saw a steady increase in black employment in the auto industry, as Detroit experienced a twenty-fold increase in its black population between 1910 and 1930.

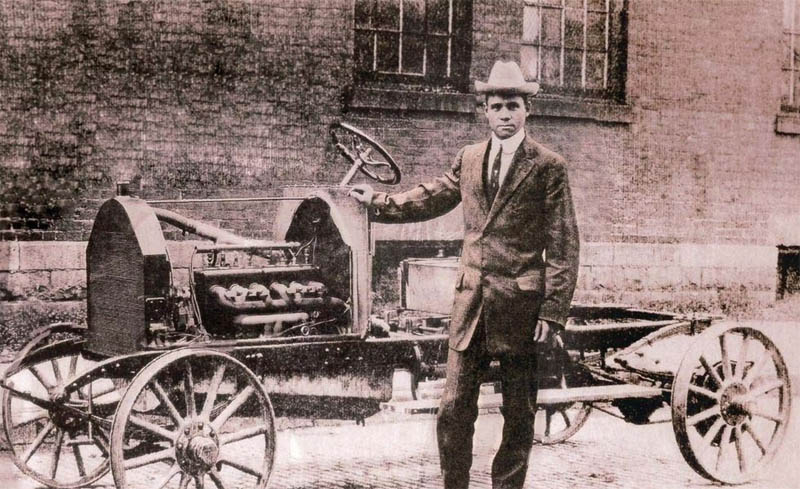

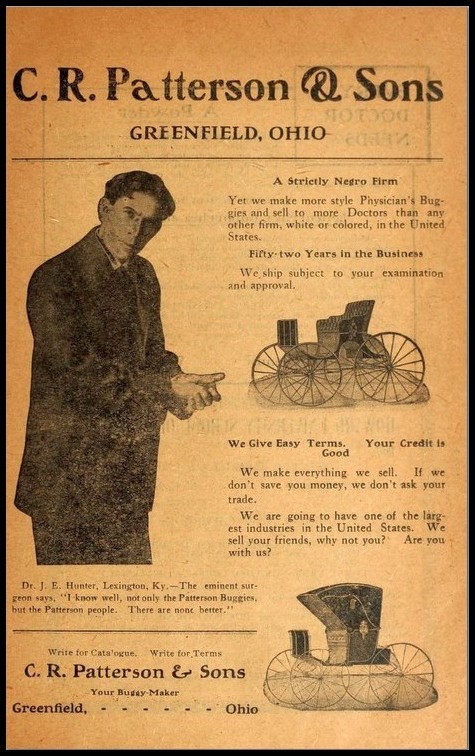

The early hostility of the manufacturing industry towards black employment did not prevent individuals from innovating their own industry; far away from the urban industrial centers of the Great Lakes, ten miles north of Highway 50, the rural town of Greenfield, Ohio, hosted America’s first (and only) black-owned and operated automobile manufacturer. C.R. Patterson & Sons, co-founded by a former slave, began manufacturing traditional carriages in 1865. Under the leadership of Patterson’s son, Frederick Douglas Patterson, the company adapted to automobile manufacturing, becoming the largest of such in the state of Ohio. Frederick Douglas Patterson (Not to be confused with the founder of the United Negro College Fund by the same name) was a man of considerable first accomplishments. Only able to attend the local white high school after his parents sued the school district, he arrived as their first black student and graduated as their first black valedictorian. He went on to become the first black football player at Ohio State University as well as class president in 1893. He was a contemporary of Booker T. Washington as a member of the National Negro Business League, served as “Worshipful Master” at the Greenfield Freemason Lodge, and was a prominent member of the Ohio Republican Party.

The company eventually retooled for commuter bus fleets, providing early buses for the cities of Cincinnati and Cleveland. Unfortunately for Patterson, the freedom to access urban markets worked in both directions; the highway system put small companies in direct competition with the emerging urban assembly lines of the 1920’s powerhouse of Detroit. Even while producing 400-600 vehicles per year, C.R. Patterson & Sons, like most small auto manufacturers, could not compete with the assembly line production of mass-market vehicles. Coupled with losses during the great depression, C.R. Patterson & Sons closed shop in 1939 after 74 years in business.

Manufacturing jobs were not the only avenue by which black Americans made economic gains in the automobility network. By 1940, blacks owned more than a third of Esso (today’s ExxonMobil) service station franchises, and the company was a leader in distributing Green Books through its stations. While the examples of C.R. Patterson & Sons and Esso demonstrate the possibilities available to some black Americans in this era, these outcomes were far from typical.