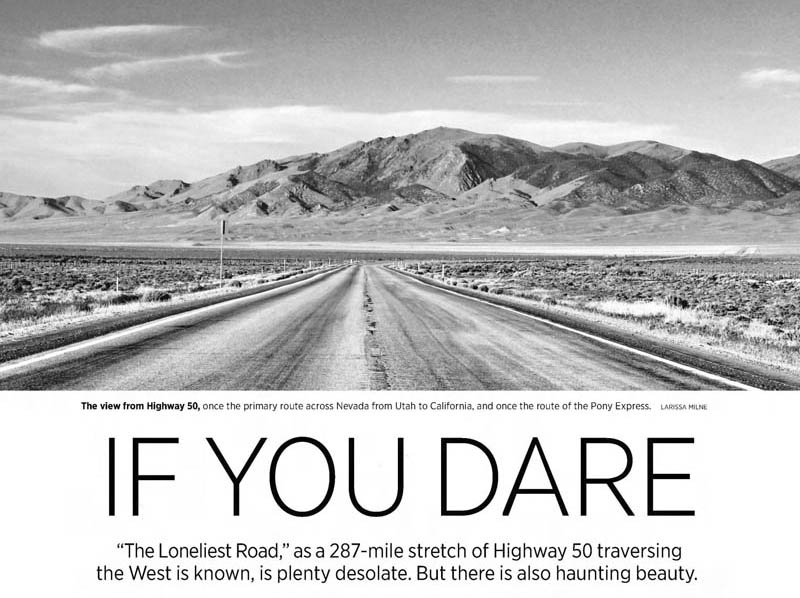

The Interstate system overwhelmingly avoided Highway 50’s corridor, rendering it a living museum to the cultural network left behind by the Interstate revolution. Culture, within the automobility framework, follows a similar pattern to the fueling network. Highways are a pipeline for cultural transmission from country to city, where culture is refined, homogenized, and redistributed back to countryside. Music, televised narratives, human settlement patterns, and trade networks each principally followed the highway pipeline to connect disparate urban and rural cultures, and are strongly influenced by the values of automobility along the way. As folk and blues musical genres exported from country to cities in the form of hillbilly and race, they evolved into separate tracts of country and R&B, only to later reunite in rock and roll as automobility values became mainstream.

Rural narratives followed a similar path in the hands of urban television writers. The highways influenced technological culture as the internal combustion engine evolved from an element of rural

utility to one of urban luxury, establishing itself as the dominant technological feature in American society. Trade networks evolved out of Appalachian Development Corridors and rum running bootlegging routes into franchise uniformity to the peril of the independent entrepreneurs of Ocean City and rural auto manufacturers in Southern Ohio alike. Urban planners’ efforts to create pastoral utopias through suburban development omitted the value of sustainability that enabled rural residents to endure generations of hardship. The distant Interstate system amplified all these effects, resurrecting a model more akin to the river, canal, and rail systems the highways were meant to replace.

The highway system, as a network, generates the value of freedom above all others. While this value of the highway has been popularly explored in the subjective world of literary and musical

narratives, its most useful manifestation is the highway’s ability to enable individuals the choice of where to live and where to work, despite geographic obstacles, by significantly reducing the economic challenges to intra-national migration. The traditional consideration of automobile ownership as an economic barrier to the highways crumbled quickly as bus services extended routes into the countryside and hitchhiking came into vogue.

Individual named and numbered Highways are ultimately arbitrary concepts. The idea of an individual highway is a metaphysical notion, held only in the minds of the idea’s adherents. This is a status shared by political borders; from a historical perspective, Highway 50 can be conceived of as a nation in itself. As virtually all streets in America are interconnected, every road could also be seen more practically as a single highway. American highways are consistently re-routed, decommissioned, and in many cases bulldozed-over by the Interstate system. Yet since the era of early traces and trails, Americans have expressed a habit of naming and sentimentalizing their routes, regardless of their pragmatic or bureaucratic origins. As the nation’s enduring nostalgia for Route 66, formally decommissioned in 1985, demonstrates, belief in a Highway is ultimately an act of faith, one in which most Americans choose to engage.