The success of the U.S. Numbered Highway System seeded its own downfall; by mid-century, the highways simply became too popular for their own good. America’s wholesale embrace of car culture created widespread social and environmental ills as traffic clogged small towns and large cities alike. Highway planners originally routed numbered highways along existing roads into the centers of towns and cities, logical destinations in the era before mass congestion. Traffic, noise and accidents motivated later road planners’ decisions to route new highways around towns rather than through them. Interstates required new construction, and typically followed engineered surveys, rarely taking into account local settlement patterns. In the 1950’s and 60’s, broad sectors of industry and government widely supported the Interstate system that subsequently dominated America’s cultural landscape.

America’s most popular highway, Route 66, was unceremoniously plowed over and largely replaced by Interstates 40, 44, and 55. While Highway 50 largely escaped this fate, its entire corridor now faces direct competition with the more efficient, safer, and consistent Interstate Highway System, a similar economic destiny to C.R. Patterson & Sons and the independent women entrepreneurs of Ocean City. Perhaps an ironic turnabout in economic history, the limited-access Interstate expressway system mimics early named auto trail routes, which envisioned a highway as an isolated line between two cities with a series of subscribed destinations along its path. This pattern is also analogous to the economics of river, canal, and rail transportation, where rural development was determined according to proximity to transportation network outlets. Similar to top-down suburban planning, the Interstate system did not allow for spontaneous roadside developments. Corporate franchises, able to afford the now commodified land surrounding freeway exit ramps, succeeded autocamps, roadhouses, and farm stands that once emerged at crossroads and river bends along old numbered highways.

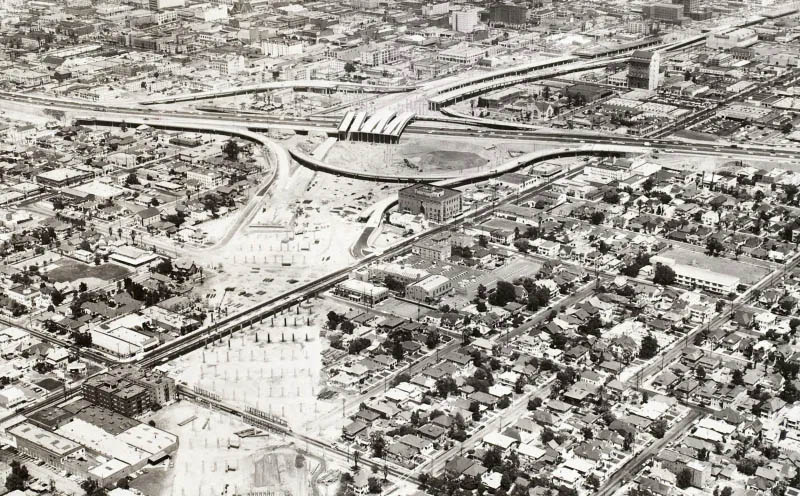

Eminent domain, the mechanism by which many Interstate routes obtained their land from private owners, affected Nevada ranchers and St. Louis ethnic neighborhoods alike. As the national economy and culture followed the Interstate, those parts of the country not covered by the system found themselves under-served by the accelerating trend of interconnectivity. The limited-access nature of the Interstate system gave it an increasingly urban focus. From an economic standpoint, the Interstates follow a colonial model compared to the more free and spontaneous numbered highways, favoring homogeneous off-ramp corporate franchise economies over independent local businesses.

Today, the United States Numbered Highways and the Interstate Highway System exist together as complimentary networks. The Interstate system has assumed economic and cultural primacy over the course of the last few decades, at the expense of small-town economies. The process has unevenly polarized the evolution of the urban-rural cultural divide, presenting as hyper-homogenization of culture for the majority of people who live along Interstate corridors, while regressing the divide’s narrowing trend for the geographic majority of America not served by the Interstate system.