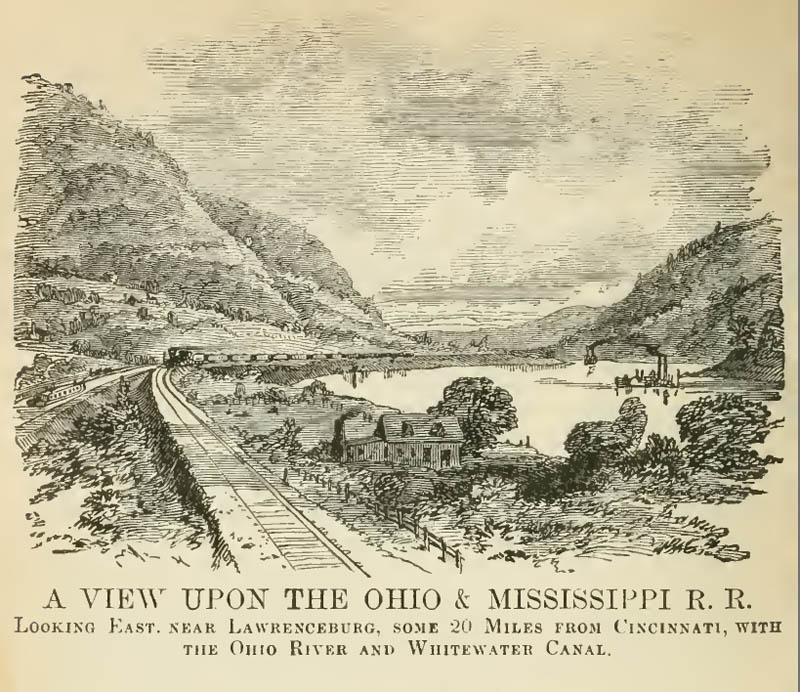

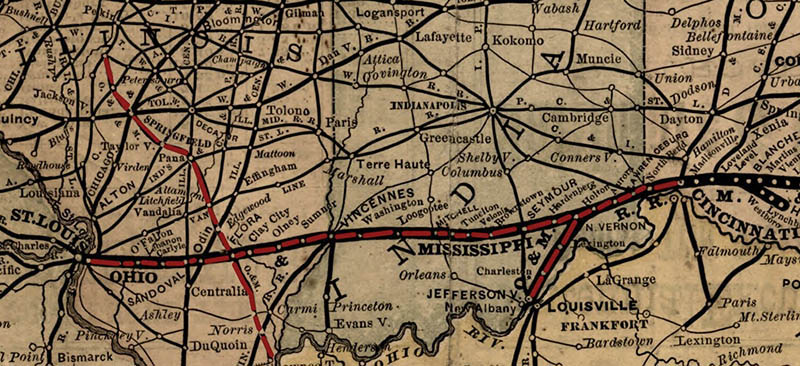

Highway 50 leaves Cincinnati along the course of the Ohio and Mississippi Railway, the westernmost branch of the eastern railroad network at the time of its creation in 1857. This passage of the O & M Railway through Indiana gained early infamy as the location of the first three peacetime train robberies in the United States, all of which were committed by the notorious Reno Brothers Gang of Jackson County between 1866 and 1867.

The American railroad network reached its zenith around the same time as the arrival of the U.S. Highway System. Early highway routing took advantage of existing railroad courses, which typically followed the most efficient engineered routes. Compared to the private railroad network’s often-arbitrary selection of station towns, the highway system offered spontaneous extensions into rural areas, allowing for economic development on a far more democratic scale. The modernization and rural reforms embodied in the highway system exemplified a triumph of the Progressive Era from which it emerged, permanently etching 1920’s progressive values onto the landscape of the United States.

Progressivism, however, had its dark side. The 1920’s saw millions of white Americans casually joining the Ku Klux Klan as one of a litany of popular middle-class gentlemen’s clubs. The KKK embraced some of the Progressive Era’s most radical political policies, bolstered by then-popular racial science, eugenics, an honor-based platform for the advancement of women, and an absolutist pro-temperance stance. The resurgence of the decades-long defunct KKK appealed to would-be Klan members intimidated by both black Americans’ migration into Northern cities, as well as increasing numbers of foreign immigrants into the United States. The Klan’s 1920’s incarnation was popular in midwestern urban areas compared to its first manifestation, with roughly half of its members living in cities between 1915-1944. Its hardline pro-temperance stance put its rural branches in direct confrontation with cottage-industry moonshiners. In 1926, Highway 50 arrived in the region of Southern Illinois finding the area gripped by violent regional conflict between rival moonshining gangs and the KKK. Criminal gangs controlled the moonshine industry, regularly fighting each other in increasingly deadly skirmishes. With the arrival of the Klan, two of the dominant criminal rivals in the area, Charlie Birger and the Shelton Brothers Gang, briefly united against their common enemy, routing the KKK in Southern Illinois and permanently diminishing its influence in the region.

Highway 50 served as an informal divide between southern Illinois’ bootlegging region, and the north, where all roads led to Chicago’s bottomless moonshine market. Illinois’ bootlegging network fit well within the automobility framework, using highways as an economic pipeline from countryside sources of moonshine production into cities, the major consumers of illicit spirits. Speed, as a value of automobility, saw network-wide gains in this era, borne from the necessity of rum runners, members of the moonshine transportation network, to convey their illegal cargo as quickly and inconspicuously as possible. Rum runners stripped their vehicles of all but the absolute necessities to keep up the appearance of normalcy in the eyes of law enforcement while simultaneously reducing weight to keep the heavily-laden autos moving at maximum velocity. This process became a competitive field for the rum runners, resulting in the birth of the stock car racing subculture, an initially rural phenomenon which quickly spread nationwide. Moonshining and stock car racing subcultures firmly established themselves, such that both survived the passage of the Twenty-First Amendment and subsequent end of prohibition. The 1948-founded National Association of Stock Car Auto Racing (NASCAR) emerged directly from this subculture and celebrates the automobility values of speed, freedom, and independence to this day. Remaining true to its rural roots, NASCAR continued to race on red-clay dirt tracks for its first three years before paving its tracks.

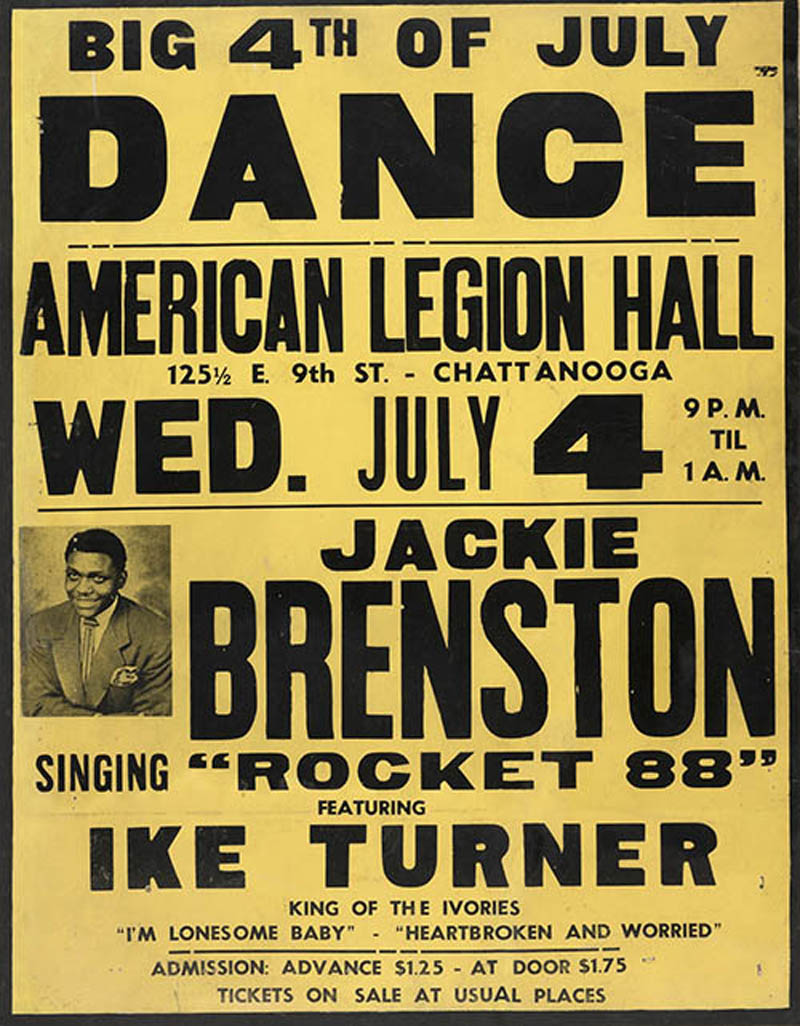

NASCAR’s homologation process, requiring all competing vehicles to be based on stock cars available for sale to the public, resonated on the consumer auto market; racing performance became a venue by which consumers judged vehicles, and auto makers responded by increasing engine horsepower well beyond the range of consumer’s earlier utilitarian needs. In 1949, a year after the creation of NASCAR, Oldsmobile released its Rocket 88, the first consumer-edition muscle car, inaugurating a decades-long fad. Ike Turner and Jackie Brenston’s 1951 car song by the same name is considered one of the first rock and roll songs. (Controversially the first, by many music scholars) The hybridized genre of Rock and Roll music reunified the styles of country and R&B following their decades-long racially segregated tours of the urban sphere, and was a direct product of the highway’s network of automobility.

Comments are closed.