** Movie spoilers ahead **

1971’s Vanishing Point, starring Barry Newman and filmed mostly on or near Highway 50, is a nearly-forgotten masterpiece critiquing the counterculture values of the late-hippy era. The film is the story of a Benzedrine-fueled police chase down the loneliest road in America, from Colorado to California, for no reason than the desperate rush of an adrenaline junkie responding to society’s mishandling of his past honor with seditious rebellion.

The protagonist, a mononymed Kowalski, emblemized the cultural nihilism of that moment in American history – he is an ex-Vietnam veteran and Medal of Honor recipient, an ex-stock car driver, and an ex-cop, dishonorably discharged for challenging his corrupt superiors. Kowalski was ex-everything that idealized masculinity projected in his era, and now stripped of those ranks, he lashes out onto the world in drug-fueled rebellion with no clear motive other than pure impulse; the implied metaphor for American culture at the time is clear.

While critics have consistently dismissed Vanishing Point as a shallow, testosterone-laden money-grab, its deeper existential metaphor and social critiques were lost on most reviewers. The film’s motifs of rebellion, liberation, and institutional corruption are well-seated in its screenwriter’s biography: Vanishing Point’s screenplay was written by none other than Cervantes Prize laureate, and author of Three Sad Tigers, Guillermo Cabrera Infante. Cabrera began his career as a Cuban revolutionary, rising the ranks under Fidel Castro, but was eventually censored in communist Cuba, resulting in his self-exile to fascist-ruled Spain. Enduring additional censorship under Franco, he ultimately landed in London just four years before Vanishing Point’s 1971 release. Having lived under two brands of totalitarianism, Cabrera’s script is a critique of the authoritarian underpinnings that were growing from the cultural nihilism of both American countercultural movements and the western intelligentsia alike.

Vanishing Point’s standout feature is its philosophical and mythological framework. Cabrera hybridized the Greek myth of Sisyphus and Homer’s Odyssey in crafting the character of Kowalski, and used the setting to critique American society and specifically the growing schism within the existentialist philosophies that were leading the counterculture of the era.

The elements of Homer’s Odyssey are readily apparent in the plot, as Kowalski repeatedly rejects tempting siren calls of lecherous women threatening to obstruct his journey. Vanishing Point was also a breakout role for actor Cleavon Little as blind radio host Super Soul, who aids Kowalski by broadcasting the pursuing police’s strategies across the Great Basin. As Kowalski’s ethereal guide, Super Soul is a blind man with the gift of music and lore, standing in for the Odyssey’s Demodocus. Three years later, Super Soul actor Little would leave an indelible mark in Hollywood infamy as the lead role in Mel Brooks’ Blazing Saddles.

For the crimes of enchaining death such that humanity would never suffer its sting, and for exposing a corrupt affair between the gods, Greek mythology’s Sisyphus was condemned to push a boulder to the top of a hill, only to watch it roll back to the bottom each time, for eternity. Similarly Kowalski defied death as a soldier and professional racer, learned contempt for it witnessing his lover drown, and stood up to his corrupt police superiors to prevent a sexual assault. Kowalski’s past resulted in his dishonorable discharge from the police force and subsequent life of delivering cars from Colorado to San Francisco and back along the loneliest road in America.

The philosopher Albert Camus used the myth of Sisyphus to convey his absurdist philosophy as an antidote to the nihilism of the modern era. Rather than despairing through his meaningless condemnation, Camus suggested “One must imagine Sisyphus happy.” Kowalski’s assured smile as he speeds towards oblivion reflects precisely this philosophy, rendering him an “absurd hero” of his generation.

The many people Kowalski encounters on his odyssey are all social dropouts- hippies, bikers, street racers, and religious zealots. They are aligned with him as members of the counterculture, but Kowalski’s distinction, which keeps him returning to the highway, is that he is just fine with the corrupt system the way it is; rather than dropping out, Kowalski delights in his role as an active rebel, not hiding from the police but antagonizing them as often as possible. All of these characters are rooted in nihilism, but their relationship to each other is an allegory for the 1960’s philosophical schism between the post-structuralist existentialists who followed the emerging tradition of Jean-Paul Sartre, and the adepts of Albert Camus’ absurdism. Sartre advocated the Marxist tradition of permanent revolution regardless of human cost, whereas Camus argued for rebellion over revolution, maintaining that Utopian ends did not justify means such as terroristic violence against civilians. This intellectual distinction would not have been wasted on Cabrera, who lived under two brands of totalitarianism in communist Cuba and fascist Spain and now found himself in the liberal Western world.

Whereas Kowalski encounters the rest of the counterculture rejecting the system to live on the periphery of society in a state of permanent and futile revolution against mainstream hegemonic values, Kowalski himself embraces the system head-on, fueling his rebellion with the futility of his own existence. He is not frightened by the systemic injustice or nihilism that has continuously dethroned him, he is excited by it. His life, and total acceptance of his inevitable death, is an act of rebellion that Camus would be proud of.

Kowalski blows through stop signs without regard for the power structures they represent. Super Soul defiantly dances in front of a large stop sign outside his studio’s window, unaware it’s even there. Meanwhile the Utah State Troopers pursuing Kowalski abruptly pull over just as they are finally overtaking him, revealed moments later due to the “Welcome to Nevada” sign that signals their jurisdictional limits. Signage, and the arbitrary authority it represents, is a character of its own in the film.

Moments before the film’s finale, the camera lingers on yet another stop sign Kowalski speeds through. The next scene is Super Soul’s single word finale, a pleading “STOP!” yelled towards the sky, suggesting the limits of the power of rebellion. Literal suicide is the ultimate act of rebellion against reality, but it is one Camus argued strongly against. In becoming the ultimate rebel, Kowalski misses the vital lesson that any path of pure rebellion will inevitably lead to suicide if not tempered.

A subtle visual cue in the film’s opening, as Kowalski charges towards the bulldozer-barricade, is a black car passing Kowalski in his final moment, headed in the opposite direction. Given the barricade, the black Ford LTD could not logically be coming from anywhere. The camera freezes on the moment of the two car’s passing, zooms in, Kowalski’s car fades from existence, and the camera then follows the black Ford in the opposite direction before the rest of the film begins as a flashback in Colorado. This scene lasts only a few seconds but is pivotal to establishing the premise that death brings Kowalski back to Colorado to begin his cycle anew.

Vanishing Point highlighted Highway 50’s route through central Utah and Nevada, and was filmed as construction began on the section of Interstate 70 that would ultimately bypass much of 50’s parallel route. In a sense, the film is a time capsule to the last moments for hundreds of miles of the highway, perhaps a final sentiment of righteous rebellion against the hegemony of the coming Interstate culture. The opening scene and finale were filmed in Cisco, Utah, re-imagined as a California border town.

While Vanishing Point had deep cultural and philosophical influences, the movie itself went on to substantially influence American culture as well. Movie car chases have existed since film’s emergence as a medium, but of Vanishing Point’s many contributions is being the first film for which the car chase was the entire premise, unleashing a genre that extends to today’s Fast and Furious and Mad Max film franchises.

Kowalski’s car, a 1970 Dodge Challenger R/T 440 Magnum, brought as much of a presence to the screen as the star of the film. Vanishing Point surged public demand for pony cars – affordable high-performance smaller models such as the Ford Mustang, Pontiac Firebird, and Chevy Camaro, bringing the performance craze instigated by true muscle cars within reach of the working class. America’s growing cultural dependency on these performance vehicles proved to be a point of geopolitical vulnerability two years later when the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) enforced an oil embargo on countries that supported Israel during the Yom Kippur War of the same year.

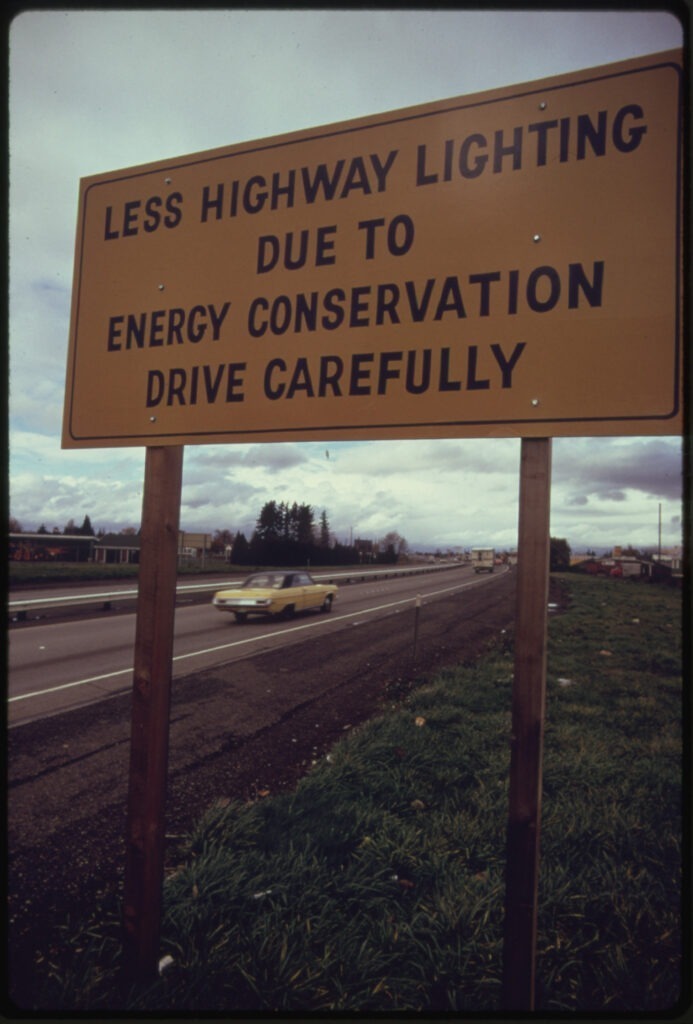

The embargo skyrocketed the price of gasoline while producing shortages and demanding fuel rationing nationwide. The results in the United States were long lines at gas stations, electricity rationing, and the 1974 Emergency Highway Energy Conservation Act which enacted a National Maximum Speed Limit, forbidding states from allowing highway speed limits over 55 miles per hour in order to reduce fuel consumption. The controversial regulation endured until 1995.

The 1973 Oil Crisis momentarily chilled the pony car craze and eventually shocked the majority of Americans into valuing fuel economy over performance. Despite a brief resurgence in pony car demand towards the end of the 1970’s (led by Vanishing Point’s cinematic descendant Smokey and the Bandit and television’s Rockford Files and The Dukes of Hazzard) the tide ebbed with the turn of the 1980’s and the era of economy vehicles became a dominant feature in American culture thereafter.

Although Vanishing Point has passed into further obscurity with subsequent generations, and its “product of its era” classically liberal attitude is dated by modern standards, the exaggerated cry of the name Kowalski has long lingered as an inside joke among auto mechanics and racing enthusiasts to this day.

Vanishing Point’s star, Barry Newman, passed away in early 2023 at the age of 92.