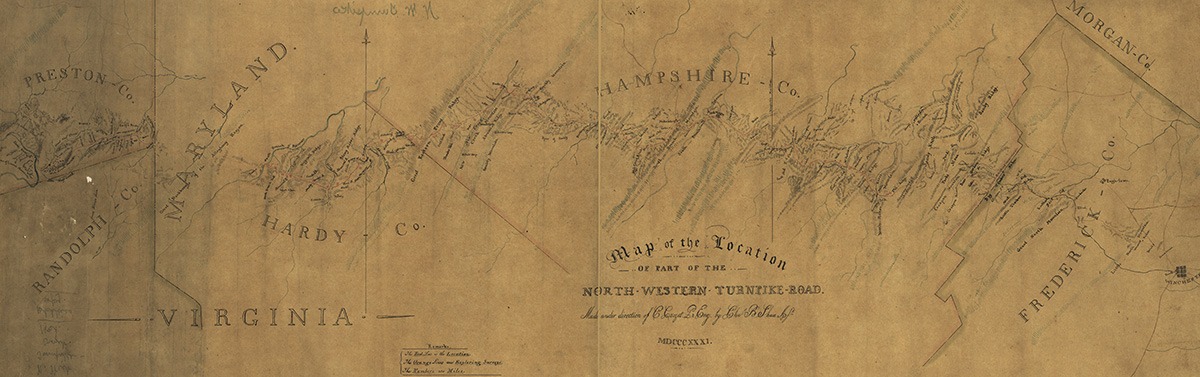

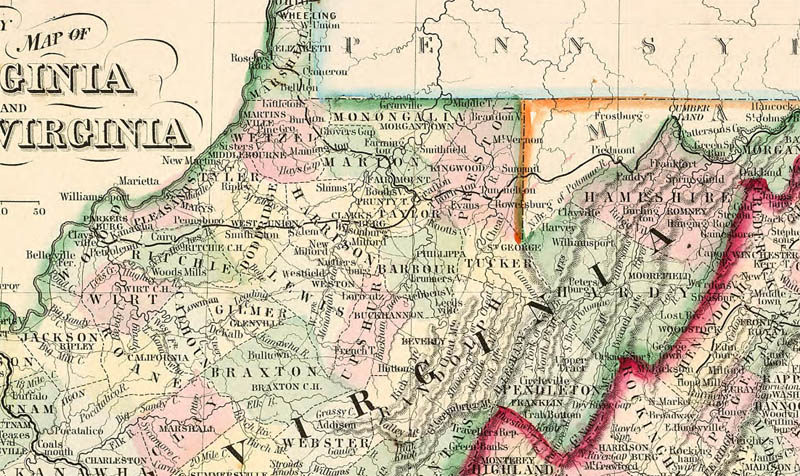

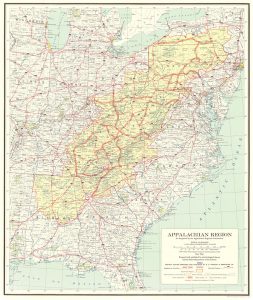

Highway 50’s route from the Potomac basin into Appalachia follows the course of one of America’s oldest formal wilderness roads, the Northwest Turnpike. Following a rare east-west trace transecting the meridional Appalachian mountain range from Fredericksburg, Maryland to the Ohio River, from its earliest days the road acted as a pipeline between Northern cities and the frontier Trans-Appalachian west. The region’s overall geographic impenetrability guaranteed the endurance of its hyper-rural character for generations. Engineered highways of the twentieth century, able to traverse rugged terrain, ultimately overcame the Appalachian’s natural barriers otherwise impossible for rails or canals to breach. The north-south orientation of Appalachian ranges and valleys eased migration from Pennsylvania and the north compared to frontal approaches from the east, while the land’s rugged nature rendered cash-crop plantation economies untenable; both factors influenced the region’s political distinctiveness, combining with the land’s remote character to produce a unique cultural amalgamation.

The culturally distinct nature and provincialism of the region led to its consideration as a wholly separate colony years before the United States Constitutional Convention. Residents of the region proposed partitioning the frontier mountains as a fourteenth British colony, Vandalia, in the mid-eighteenth century. Following the Revolutionary War, a likewise movement called for a fourteenth state called Westsylvania; both movements roughly covered today’s West Virginia, and were met with significant opposition from their respective governments. West Virginia ultimately gained its status as an independent state when it seceded from the Confederacy to join the Union during the height of the Civil War.

Federal and local efforts improved roads into far reaches of Appalachia, opening doors for cultural exchange with the once-isolated hillbilly culture that thrived in the region despite generations of hardship. The new highway system thereby enabled one of the most significant episodes in American music history. In 1933, Library of Congress folklorist Alan Lomax began driving his Plymouth, outfitted with a portable recording studio, into the depths of rural America to collect its musical heritage, forever changing the course of American music. While focusing on the Appalachians, Lomax’s musical odyssey took him to dozens of remote enclaves from southern Florida to Michigan’s upper peninsula until his car was “literally falling to pieces.” Lomax’s on-the-road “discoveries” of Muddy Waters, Woody Guthrie, Lead Belly, and Pete Seeger, to name a few, brought American folk and blues music to generations of people far removed from their rural origins. The Lomax recordings sowed seeds nationwide of the musical genres hillbilly and race, which later evolved into country and R&B. Lomax made recordings in at least eight locations along Highway 50.

Despite its nationally-recognized cultural contributions, Appalachia’s sparse population and rugged geography presented significant economic challenges for the region. Pursuant to President Johnson’s 1960’s “Great Society” initiatives, the Appalachian Development Commission’s Highway System designated Highway 50’s course from Harrison, West Virginia to Athens, Ohio Corridor D, allocating federal funds to highways in this region largely avoided by the Interstate system for its engineering challenges. The program created 21.8 billion dollars of additional income for the Appalachian region in the subsequent fifty years, increasing annual per-capita incomes by almost $600, while generating 31.7 billion dollars for outside regions. The program economically enriched Appalachia, as trade with outside cities proved increasingly lucrative for both sides of the divide.

Comments are closed.