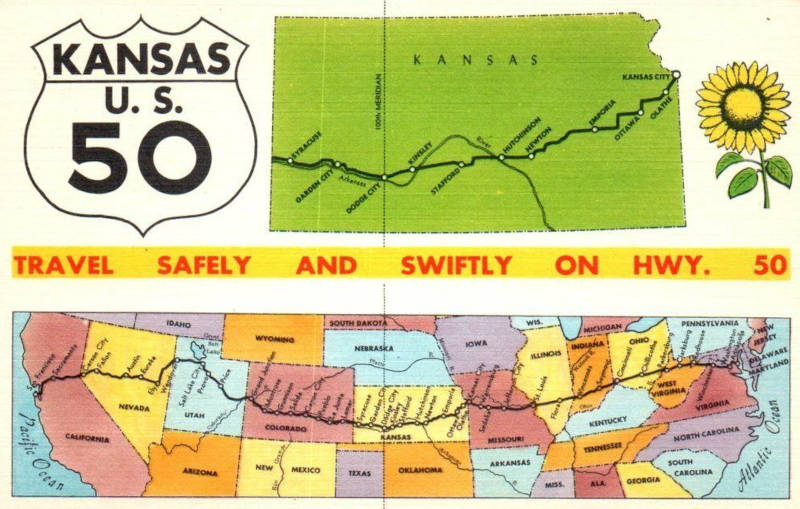

The lame duck period of the American presidency, originally a four-month span between an election and the formal transfer of executive power, is largely a vestige of the poor condition and impassibility of colonial-era roads; it was expected to take as long for both news and electors to travel across the thirteen colonies. 1935’s Twentieth Amendment to the Constitution shortened the lame duck period by two months, emerging in an era when highways and the technologies following them progressively accelerated all aspects of American life, including politics.

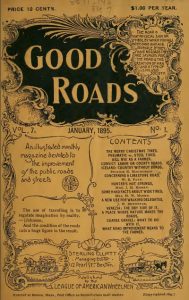

The Good Roads Movement, beginning in the early 1880’s is the element most responsible for this acceleration. Despite the United States’ long-established reputation for poor-quality roads, this first organized movement to improve the nation’s roadways did not emerge until a bicycle craze swept the country during the 1880-90’s. The urban elites who popularized bicycling initially led the movement to build better roads for the sake of their own bicycles, not intending them for the rarely-seen automobile. The movement’s national newsletter, Good Roads Magazine, began publication in 1882 and demonstrated the effectiveness of the Good Roads movement’s influence through featured endorsements and articles written by prominent politicians and jurists, including future President William McKinley.

The movement’s early goals included securing federal involvement in funding public road improvement, as the federal government was the only entity with the financial means and impetus for common-good projects capable of financing such an expensive undertaking. Beginning in 1893, Congress created the Office of Road Inquiry, largely due to the efforts of bicycle manufacturer Albert Pope, whose personal fortune, vast connections, and flair for theatrics culminated in sending an over-sized petition of 150,000 names to Congress on two rotating spools tall enough to dwarf most people. Pope made charmingly compelling public arguments, such as his 1890 suggestion that the condition of the American road “probably gave rise to the theory of ‘survival of the fittest,’ because it would kill any ordinary mortal to ride over it.” By 1905, the Office of Road Inquiry confirmed the federal government would play a significant role in road construction, and adopted the more formal title of Office of Public Roads. The bureau endured three more name changes and a shuffling of positions in the Federal hierarchy until 1966 when its duties finally landed under the umbrella of the new Federal Highway Administration. Agency nomenclature was only a superficial reflection of the rapid pace at which systemic change occurred in the United States in this era.

The bicycle craze inspired the emergence of the first production-level motorcycles, which quickly evolved into automobiles. Wealthy bicycle enthusiasts rapidly embraced automobiles, and their early adoption of electric automobiles in particular made them a common sight on America’s city streets by the 1900’s. The ongoing successes of the Good Roads movement enabled further innovations in transportation; better roads for bicycles turned out to be just as good for automobiles. A nationwide explosion in highway improvement enabled city residents to freely explore beyond their city’s limits, shifting consumer desires towards vehicles with greater range. The limited battery capacity of the electrics of the era simply could not compete with quickly-refuelable internal combustion engines most commonly seen on rural farms. As consumer tastes in vehicles changed to emphasize the significantly longer-ranged internal combustion variety, electric vehicles quickly fell out of vogue for the rest of the century. The pleasure-touring urban gentry now adopted the noisy, hard-to-start, petroleum-powered internal combustion engines, previously a consort of the working farmer.